Chapter 4: Reflexive Scripted Design:#

Network / Intersect

Overview#

This thesis has so far presented scripting as a computational process, and as a mode of instructing performers. This chapter proposes an original process called ‘Reflexive Scripted Design’ for creating novel works, using the film Network/Intersect as a prototypical example. The film was created via the creation of a script-ruleset which enabled its form to wholly reflect its content; this 'script' was followed throughout the entire production process from initial concept to editing. 'Constrained scripted design' represents an original contribution to knowledge – a methodology that can be applied to other performative architectural designs, and as such will be developed further beyond the context of this thesis.

Project videos#

Network / Intersect video

As displayed in Seoul Museum of Art, April-May 2016

Best watched in full-screen, with headphones / auto-loops

Context#

In January 2014 I went to see a play by the immersive theatre group Punchdrunk. Entitled The Drowned Man: A Hollywood Fable, the performance took place in a large 5-storey building, formerly a Royal Mail sorting office, next to London Paddington station.1 Each member of the audience was given an identical white mask to wear, and during the performance was free to roam the set of a ‘town’ which had been constructed inside the warehouse to mimic the outskirts of early 1960s Hollywood. The audience could walk in and out of houses, pick objects up, read letters, look in drawers, and follow the (unmasked) performers around as their characters went about their fictional lives.

The performers' scripts led them in a highly choreographed journey around the entire building, from one floor to another, from the David Lynch-styled nightclub and the Foley studio in the basement to the shops, bar and cinema on another, to another's film sets, or the top floors' desert and chapel. The audience would individually choose a character to follow, witness their interaction with another character – for example, a fight – then have to choose which character they wanted to follow next as the two ran off in opposite directions. Or, they could follow nobody, and just explore the world that Punchdrunk had created. The whole time, a spatialised soundtrack played throughout the set, different in each area, featuring fragments and sections of songs and film scores. This served a number of functions: to create a cinematic atmosphere, to 'narrate' and provide soundtrack to scenes within the play, and to give the performers subtle audio cues. The play featured little spoken dialogue from its actors, instead relying on movement, gesture, and physical interactions.

Wearing a mask, which limited my peripheral vision, whilst exploring a highly detailed world, and witnessing interactions between actors, yet not being able to interact – even being anonymised by a mask myself – felt somewhere between watching a film and playing a sophisticated video game. After the two and a half hours of the performance, I had picked up fragments of several storylines, but had experienced something that was at once beguiling, intriguing, alienating and immensely enjoyable. In short, I felt punch-drunk. I saw the production several times in order to decode its mechanics.

The play was in fact highly choreographed. It featured multiple intertwining narratives, and around 30 actors, mostly with dance or physical theatre backgrounds, going about their lives in 1960s Hollywood. The play had a looping structure, with each 'scene' being approximately 5 minutes long, and the characters running their entire ‘loop’ multiple times per performance. The storylines for the characters included young actors trying to break into the movie business, exploitative studio executives, spurned lovers, a starlet’s demotion to a non sex-symbol role, and at least one murder. Although there was a high number of characters physically inhabiting the set, there were many more hinted at through the design of the set itself. Each character had a set of spaces that they ‘belonged to’, which were laid out and filled with artefacts which reflected their personalities. This was highly exaggerated, and taken to absurd levels in some cases; the vein starlet's dressing room featured about twenty mirrors all angled to look at her; comically large piles of chicken-wire cages filled one characters' office; a caravan was filled with angst-ridden handwritten letters and actors' headshots; the security guard's office was filled with a huge number of orchids and plants.

The thing I found striking about the play was the manner by which the design of the space reflected the perspectives of its characters. It seemed to reflect Bateson’s statement that ‘human beings operate more easily in a universe where some of their psychological characteristics are externalised.’2 Had I not even seen the play, the space itself would have been able to hint at a number of the storylines that would take place inside it. I found myself determined to carry out a project in which the design of a characters' environment to reflect their own beliefs and motivations would play a major role.3

Italo Calvino expressed a similar idea in the chapter of his book If on a winter's night a traveler... entitled In a network of lines that intersect.4 The entire book is an experiment in form; every second chapter is an unrelated ‘first chapter’ from a different genre of book, based in a different culture, and written in the first-person perspective by a character whose internal state of mind is reflected in their environment. In a network of lines that intersect is told from the perspective of a businessman who sees the financial and business world as a large optical device. Using metaphors about mirrors and reflections, the character describes his shady and somewhat paranoid methods of financial deception:

They [^other businessmen] don't know that I have built my financial empire on the very principle of kaleidoscopes and catoptric instruments, multiplying, as if in a play of mirrors, companies without capital, enlarging credit, making disastrous deficits vanish in the dead corners of illusory perspectives. My secret, the secret of my uninterrupted financial victories in a period that has seen market crashes and bankruptcies, has always been this: that I never thought of money, business, profits, but only of the angles of refraction established among shining surfaces variously inclined.5

Calvino, like Punchdrunk, creates a world for his character to inhabit that reflects his internal mind-set and motivations. This particular story culminates in the character becoming lost in his own hall of mirrors, his identity merging with that of those was trying to deceive; the lens through which he saw the world became his own downfall.

As discussed in earlier chapters, Calvino was well known for his experiments in form, both before and during his time as an Oulipian. The extreme constraints he placed on the form of his work in If on a winters night a traveler… spanned from the style of writing and entire world-view shifting completely every other chapter, to the overall structure of the book, which follows a rule of thematic inversion: the last chapter was an inversion of the first, and so on. These ideas of constrained, ‘scripted’ processes (following a ruleset in order to create works) were another element I wanted to explore as a creative tool within a project, following the trajectory of projects presented in this thesis that all use the idea of the ‘script’ (computer scripting / scripted performance / scripted design process) in one or more ways. This chapter presents the final project, and the prototypical instance of what I term ‘Reflexive Scripted Design.’

Part of the inspiration for the ‘Reflective Scripted Design’ process came from a workshop I attended in Punchdrunk’s studios.6 Run by designers Hebe George and Maita Jobbe Duval, who had both worked on The Drowned Man, and held on the set itself, the workshop explored design process that Punchdrunk had used in the creation of the play. One of the main things I took away was their approach to writing their performance scripts. Punchdrunk's plays are reactive to the empty buildings they are set in; the directors of the company spend time alone in a potential building before any of rest of the company see it working out what it could potentially contain. They claim not to have pre-set ideas when they 'acquire' a new property, but rather use a creative process based on intuition to guide their work.

Each play is a synthesis of three elements: two 'primary texts' and a place and time. In the case of The Drowned Man, the primary texts were Georg Büchner’s unfinished play Woyzeck and Nathaniel West's The Day of the Locust, whilst the place and time was early 1960s Hollywood and the surrounding areas.7 The synthesis of three elements creates something novel, and doesn't force the writers to lean too heavily on any one element. Once I had learnt of this technique, it seemed that it was a mode of scripting a process much in line with my research interests. I had long wanted to work on a project which would similarly create a set of worlds that reflected the internal state of characters, yet also serve as criticism of larger sociological or technical ‘machines’. Calvino’s businessman was a compelling character whose world offered promise: key to the next stage of the project would be to find other abstracted world-views.

Soon after reading Calvino’s novel, I became interested in the similar, but differenct form of abstracted world-view emerging forms of Russian propaganda which were being reported in British and American press.8 A pair of articles in the New York Times and the Guardian in 2015 present an interesting image of state-sponsored Russian propaganda in the 21st Century. In the New York Times article The Agency, investigative journalist Adrien Chen examines a propaganda agency whose aim is to create uncertainty on the internet, using social media, blogs, and online videos.9 Workers at the St. Petersberg-based Internet Research Agency (IRA) create and curate false avatars who inhabit online space. Many of these avatars run blogs, comment on news articles, and display a high level of interaction with each other, frequently commenting on each others’ blog posts, mentioning each other in tweets, and so on – creating the illusion that these avatars belong to a natural, organic community. In addition, they create false accounts of events that never happened. In the story's opening anecdote, the avatars create a social media frenzy around a fictitious chemical fire in a small town in Louisiana, using websites such as Twitter to ‘report’ on the situation in real-time, contact real local officials, and act as if the event had really happened. Other fabricated events Chen described include a racially motivated shooting, and an Ebola outbreak at Atlanta airport. The Ebola outbreak is particularly notable for the level of detail in its supporting media:

A YouTube video showed a team of hazmat-suited medical workers transporting a victim from the airport. Beyoncé’s recent single “7/11” played in the background, an apparent attempt to establish the video’s contemporaneity. A truck in the parking lot sported the logo of the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.10

This, Chen argues, is not normal propaganda. The motives behind this new mode of false information are intriguing, and something that British-Russian journalist Peter Pomerantsev investigates further in the Guardian article Inside the Kremlin's Hall of Mirrors.11 One aspect of the contemporary Russian propaganda efforts, Pomerantsev explains, is to sew stories of falsehoods in every possible media outlet, from the internet to the state-sponsored Russia Today TV channel (known as RT). The initial aim is to create a distrust in the media. However, Pomerantsev relates the overall effort back to a Russian field operations manual called Information-Psychological War Operations: A Short Encyclopaedia and Reference Guide, which he quotes:

“There are two possible approaches to information war,” the encyclopedia states. The first approach “recognises the primacy of objects in the real world” and attempts to spin them in a favourable or unfavourable direction. The “more strategic” approach, it continues, “puts information before objects”. In other words, the encyclopedia seems to be saying that reality can be reinvented.12

This is a powerful image: the idea that by spreading mistruths, the fabric of reality can be undermined.13 I began to think about the workers that Chen describes at the IRA: what do they think about the work they carry out, and how does it feel to be sewing untruths for a living? In the article, Chen describes the daily routine of the workers via a former worker he interviews; he witnesses the staff exit and enter their workplace end masse at the beginning and end of their 12-hour shifts. Knowing anything beyond the immediate task to hand, I thought, would imply that either the workers are highly cynical, or that they adopt a similarly abstract worldview to the character in the Italo Calvino story.

These issues of control, and how they affect personal freedoms, bring me to a pair of related theoretical writings: Felix Guttari's Postscript on the Societies of Control and Nathan Moore's Diagramming Control.14 Moore’s chapter builds on the central argument of Postscript on the Societies of Control – a work that proposes that Western society has moved beyond the Foucauldian idea of ‘disciplinary societies’ (epitomised by the diagram of the Panopticon), and towards ‘societies of control’ where power is increasingly abstracted and norms are ever-shifting.15 Moore has an interesting perspective on this argument: he is a lawyer who is interested in the concept of control, yet also has an interest in the built environment.16 His chapter aims to create spatial metaphors that enable the reader to create diagrams of control systems, so that a layer of abstraction is removed and they may be discussed in a spatial plane.

In the summer of 2015, the photographer Max Colson and myself were invited to run a workshop by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and UCL Urban Lab. The workshop was entitled Virtual Control, and was timed and themed to accompany an exhibition of the same title Colson was showing at RIBA (which also featured one of my art pieces).17 We took a group comprising approximately 12 members of the public and RIBA members on a guided walk from Stratford Underground Station in London, through the Westfield East Shopping centre and to the recently-opened Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Colson and I wanted to encourage these members of the public to engage with these newly constructed ‘public-private partnerships’ and investigate the implicit rules and associated behaviours that the spaces generated through a series of structured conversations – essentially, to question to what extent Guttari's Control Society had been embodied in these new built forms.18 One of the attendees was Moore; the conversations that we had on the day, and the email correspondence that followed, was of great interest to me. We discussed how the Westfield Shopping Centre in its architectural and interior design was a dense informational system which (whether it had been designed this way or otherwise) existed for the purpose of conveying meaningless messages. It presents the visitor with a seemingly endless array of novelty, creating continual confusion and causing its visitors to lose their grip on the meaning of their environment – and thus, causing them to buy more goods.19 The metaphor about Westfield was similar to that found in the articles on Russian propaganda, and a similar sleight-of-hand technique to that used by the character in the Italo Calvino story.

The ideas I had been exploring would find a concise application once I began my residency at the Palais de Tokyo. In November 2015, the Palais de Tokyo’s curator Fabien Danesi and Seoul Museum of Art’s (SeMA) Gahee Park told the 6 artists in the programme about a group show they would be curating at SeMA. They wanted us to each create a new work that in some way tied in with their exhibition title Urban Legends, and if possible, made some reference to Korea. The budget allocated was €3000 per artist, and the exhibition would open in April 2016. As part of the programme, the artists would also spend a month in Seoul in advance of the show.

Network / Intersect#

Due to the constraints of the exhibition format, its timescale, and budget, I decided that the best option would be to make a film. My time would be split between this and several other projects (86400, 24fps Psycho, and Scriptych). From the date we were given the brief, there were around 4 months until the journey to Korea; one month in Seoul; then the exhibition. Based on the time constraints, and the inevitable difficulty of producing an ambitious work in a new country where I was unable to speak the language, I decided that all filming would have to take place in Paris.

The limited budget meant that sets had to be produced cheaply, or filming would take place in public places where no permits or permission had to be sought. The budget would also limit the available crew; I could afford to pay a limited number of actors, but also had the assistance of staff at the Pavillon: Justine Emard, a practising artist and photographer, and Justine Hermant and Chloe Fricout, who would both assist with production.

Rules#

I chose to adapt the method I had learnt from Punchdrunk to determine the content: the subject matter would be inspired by the stories of Russian internet propaganda and Italo Calvino's In a network of lines that intersect; the place and time would be a contemporary Seoul. However, the practical constraints of not being in Seoul made shooting there within the time-frame impossible. In addition to the adapted Punchdrunk technique, I created a basic ruleset which I would use to make decisions throughout the project, about every aspect of the production, from its inception to the film editing.

The rules were:

-

The form of the film must reflect its content

-

Techniques of the Russian Internet Research Agency must be used where possible

-

The film must be set in Seoul

-

All filming must take place in Paris

Some of these were chosen for thematic reasons: introducing creative constraints to form and content, much like the Oulipian rules; some of the rules were for practical reasons (but also posed creative constraints). All of the rules were decided as a result of careful research, and a reflection of my own attitudes towards the subjects. Thus, I call this process of rule-creation ‘Reflexive Scripted Design.’ The term ‘reflexive’ is used as an adjective in two ways. Firstly, like Oulipian works, it focuses attention on the process and production of work, so that the rules themselves become part of the defining fabric of the project.20 Secondly, it acknowledges the role of the author in the creation of work which responds to subjects; the author becomes innately aware that the arbitrary rules created early on may have effects on the form and content of the work later, and thus the perception of the subject matter.21 ‘Scripted’ refers to the rules which are created. In using this term, I consciously embrace its myriad meanings and inherent contradictions, giving a degree of freedom to the author: like the director of a play, they can choose the level of leniency they give themselves to interpret their own rules. The rules should be created as a result of research into the subjects, places, and potentially characters to be integrated into the work, and in some way ‘site’ the project (as the Paris-Seoul relation did in this project).

Form#

The project described in this chapter serves as the prototype for this design process. Once the rules had been established, the most important thing to establish was the form the film would take. Being a film synthesising two inter-related themes, I decided to display the film on 2 screens side-by-side, with the idea that two films would be synchronised to show similar aesthetic content whilst discussing contrasting but complementary subject matters.22 The film would focus on two characters: one inspired by Calvino's businessman, the other a worker in a propaganda agency responsible for a network of avatars. Central to the propaganda agency worker's job is the adopting of multiple personas and viewpoints in their 12-hour days.23 In order to carry out this task, I decided that my character would have to adopt a mode of thinking similar to that Pomerantsev describes; to believe that reality is an illusion, and that their work is meritorious in its role in pointing this out. The mode of exploring both characters would be through showing their routines and the environments they inhabited, both of which would reflect the internal states of the characters.

The characters would also balance each other visually; one sees themselves as a master of their own destiny and is the director of a network of companies, whilst the other is low-ranking within a chaotic, and ever-moving organisation.24 I named the characters M and W, letters whose capitals are the inverse of one another. M – based on the Calvino character – would appear in the centre of the screen where possible, with low-angle cameras to imply their dominant position. Their environment would be luxurious, executive: travelling by chauffeur-driven car, meeting in marble-lined buildings and boardrooms full of dark wooden furniture. W would travel by public transport and work in an increasingly messy cubicle in a generic office building. The visual inspiration for W was largely inspired by the films of Kaufman; an atmosphere of shoddiness and chaos.25 Like most Kaufman films, many Theatre of the Absurd plays, and the Calvino story, the films would also be entropic. The central motif of both storylines would be the disintegration of the characters' sense of self caused by the abstracted lenses through which they see the world.

Since the central motif of Calvino's story is that of the mirror (the businessman has built his empire on the idea of mirrors), the films would also mirror each other – one playing forwards, whilst the other played backwards. Once they came to their end, or beginning, the direction of both films would reverse, so that the film that had previously been playing backwards would play forwards, and the previously forwards film would play backwards.26 However, this came with a challenge: in the pair of films, each one's chaotic end would have to segue into the others' ordered beginning.

These chaotic endings would differ for both characters, based on their world-views and their particular line of work, but both would revolve around issues of identity and their sense of self. W, whose character transforms into myriad personalities per day in the confines of the office for the purposes of living virtual lives online, would find these invented characters invading his non-work life; to borrow terminology from Deleuze and Guttari (via Manuel de Landa), the virtualities he created online would merge into his actuality, blurring the line between his lived reality and the fictions he creates.27 The film would show W’s daily routine becoming slowly more confused and absurd, culminating in him repeating lines of fiction to narrate his lived experience; simultaneously, he would be seen wearing distinctive costume from his characters in daily life, visually symbolising this transition. M, on the other hand, explains his business dealings in terms of mirrors and lenses, as if his whole business empire were a large machine for the creation and manipulation of images. During the film, he extends this metaphor to describe a technique he uses to ensure clients empathise and identify with him:

I imagine myself behind a one-way mirror – so that when they look at me, they see themselves: their moves and mannerisms, their hopes & dreams. The whole time my true motivations remain hidden – even from myself.

Much like the character in Calvino’s story becomes trapped in his own hall of mirrors, M becomes victim to his techniques of hiding his emotions and motivations. He develops an inability to distinguish between his own mirror image and other people, his speech merging with that of his clients in a confused, parabolic mess. The film should convey the impression that M is somewhere between mirrored self-misidentification and a Fregoli disorder.28 The two storylines feature similar forms of self-identity crisis, but resolve in different ways.

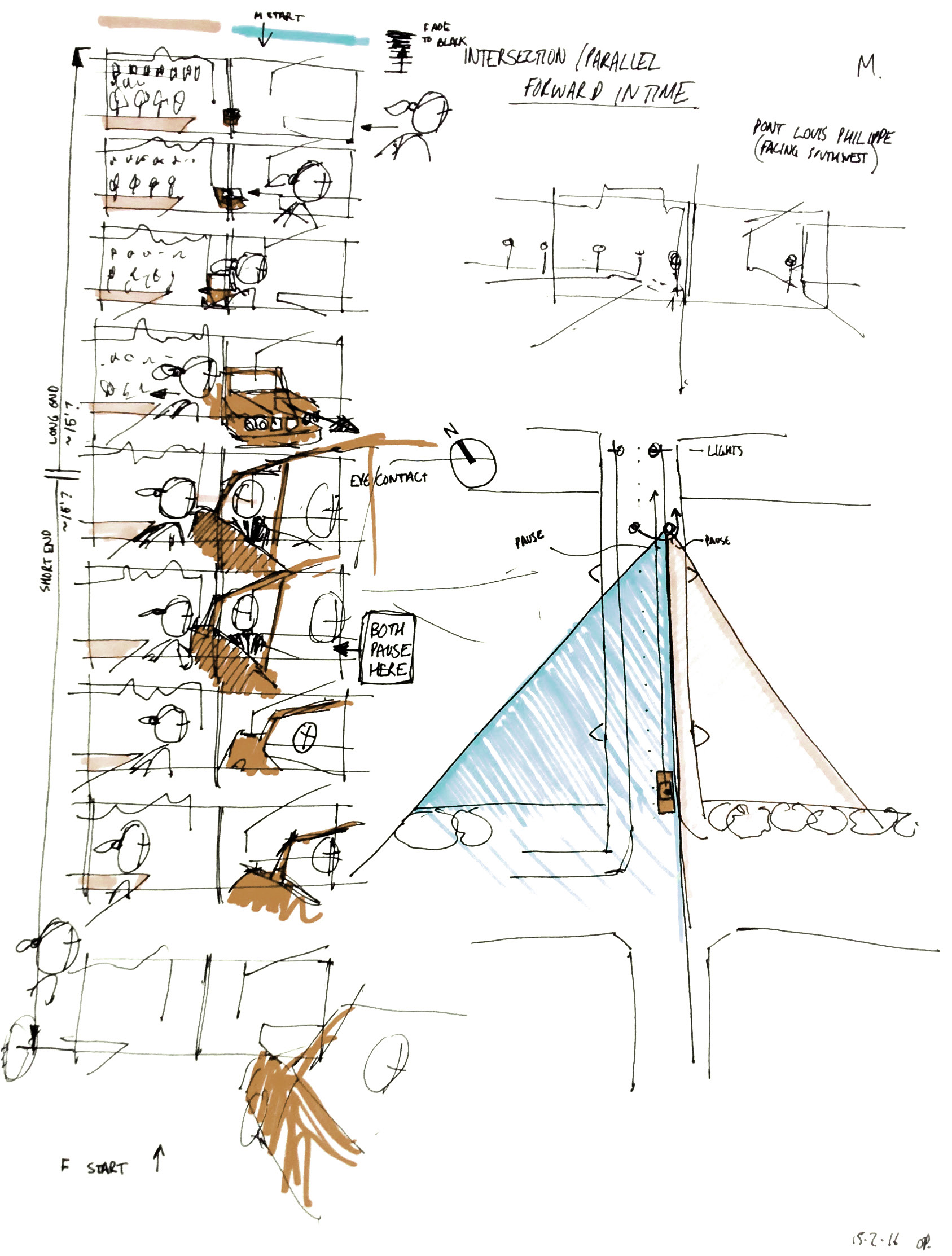

This would also mean that both films would have to be filmed with a mind to their appearance both forwards and backwards simultaneously. It took several attempts to devise a means to diagram the shots of both films in a way that ensured they could share thematic elements and transitions in both directions simultaneously. The eventual result had two main elements: a timing system, and a diagram system.

Timing#

The overall film length was to be 512 seconds; this meant each film would be 256 seconds long. I chose this time increment for two reasons:

-

W works primarily on computers. Computer memory works on a base-2 system;29 256 and 512 are numbers synonymous with computing.

-

Both numbers are divisible in the base-2 system; therefore the film could be divided into 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 or 64 second chunks. I settled on 4 seconds after doing a few screen tests. 2 seconds is too short; 8 seconds is too long. This does not mean that all shots must be four seconds, but rather a multiple of four seconds.

Diagram#

I developed a diagram system to plan shots within the films. This consisted of two landscape pieces of paper, of equal length, which had measurements printed across the bottom from one side to each other – one line to represent each four seconds of the film (256s total). The paper also had an arrow pointing left to right to signal its direction. Transitions would have to occur at 4-second markers. Read left-to-right, the storyboard acted like a film timeline. Turning the other storyboard upside-down and placing its timeline in line with the other film ensured that what was happening on one storyboard at a certain time could be synchronised with the storyboard on the other screen as well. Time could be effectively segmented into usable shot-lists.

My initial storyboards divided the timelines into equal-sized "chunks", portraying one day in the life of each character (so the films would, for example, both feature 4 64-second 'sections', each one representing a day in the characters' life). However, playing through storyboard simulations in film-editing software with script read-throughs showed that these felt like artificial constraints on natural story-telling. If each 'day' onscreen was the same length as the others, it would be hard to draw attention to any particular element as the focus of a story). The 4-second shot rule (or multiple thereof) was, however, kept in place; this enabled and enforced a modular filming style whereby each shot had a minimum of 4 seconds on-screen. When working with actors, they would be given directions for the next 4-20 seconds immediately before filming, echoing the modular way in which I envisioned W's character working in the propaganda agency ('picking up' and 'putting down' multiple personas per day).

Workflow#

The descriptions of editing and audio techniques above reflect one crucial part of the design process: workflow. A major part of film-making is the discipline and planning one puts into one's workflow: having a framework in place to shoot, gather footage, review, rate, collate and edit a film. In the case of this project, whereby the form of the project and its outcome was being determined in advance by a scripted design process, this was even more important. The operations to shoot two films simultaneously, both of which must be played both forwards and backwards, are complex. Another crucial limitation was the film's budget: I could only afford to pay the actors for a small number of shooting days (4 per actor) and there was only one day where both actors would be in the same place at the same time. The logistics of the editing operation were worked out in advance of any shooting, and multiple attempts to edit and export 'dummy' footage were tested to improve the system.

One of the main editing restrictions was the capabilities of editing software on my computer.30 Although my computer has relatively high specifications for film editing, the challenge of editing 2 high definition films in opposing directions was one with intrinsic practical issues; rendering previews of reversed film is still something that takes time. The following workflow was devised for film exports.

The final film consists of two 1920x1080 films, side by side. However, the films were edited individually, then exported as assets which were then imported into a third, master timeline. This timeline simply positioned a film file called w_latest.mov on the left, and m_latest.mov on the right. Because the films were pre-compressed (and could be exported at low resolution as they were simply to check timing of shots in editing), they could be reversed on the timeline easily. When it came to mastering the films, I simply had to export high resolution versions of W and M as w_latest.mov and m_latest.mov, then export the master film (which would collate these two films) at high resolution. The structure of the film, with the 4-second ‘chunks’, proved to create a highly restrictive editing technique. This meant that there are a few sections of the film where the pacing is not as it may have been had I been able to work outside of the confines of the scripted design process, but these limitations do reflect the working methodology of Calvino and the Oulipo.

In order to plan shots, and be able to work confidently and efficiently when actually filming, I created diagrams detailing the optical angles and focus lengths of every camera I had access to. I also shot test footage in every location that I would later use. This would enable me to plan shots more effectively for shooting.

Internet Research Agency Techniques#

Besides the technical aspects of film-making, a major component of this project was the use of techniques inspired by the Internet Research Agency. Chen reports that the last known address of the IRA was in a nondescript office building in St Petersburg, yet their workers, assumed to be near-exclusively Russian, make videos and write blogs that purport to be from America.31 Chen's example of a video supposedly shot in Atlanta airport gains legitimacy through the positioning of a truck in the video with Atlanta airport decals. Rules 2, 3 and 4 of the project stated that the film must use IRA techniques, and be shot in Paris but set in Seoul. By shooting in Paris-as-Seoul, I was also fulfilling the IRA technique: in the same way that it could be assumed that most of the IRA workers had not visited the USA, I had at that time not visited Korea. Therefore, like the IRA workers, I would have to use the tools of the internet – Google Street View, Flickr, Google Translate, and more – to learn what my version of Seoul should be.

One step towards creating a fake Seoul was to find the people to inhabit it: the actors to play W and M. I had, for the first time, budget to pay actors, so set about placing adverts written in Korean and English in the artist residences where I lived, on Facebook and the internet. Through a network of contacts, I managed to gain enough applicants to hold auditions, and chose to cast two actors: Hokyoung Kim, a Korean actor visiting Paris and looking for work, and Patrick Ng, a Hong-Kong-Dutch actor.32

The easiest film to shoot in a fake Korea would be M, an executive who would be seen riding in chauffer-driven cars and in luxury offices. Interiors of offices would be filmed in the Palais de Tokyo; in sets I would construct in the the Pavillon studio, and on the marble staircase of the 1937 building. One shot in particular – of M descending a staircase – echoes the Russian Constructivist photographer Aleksandr Rodchenko's The Stairs.33

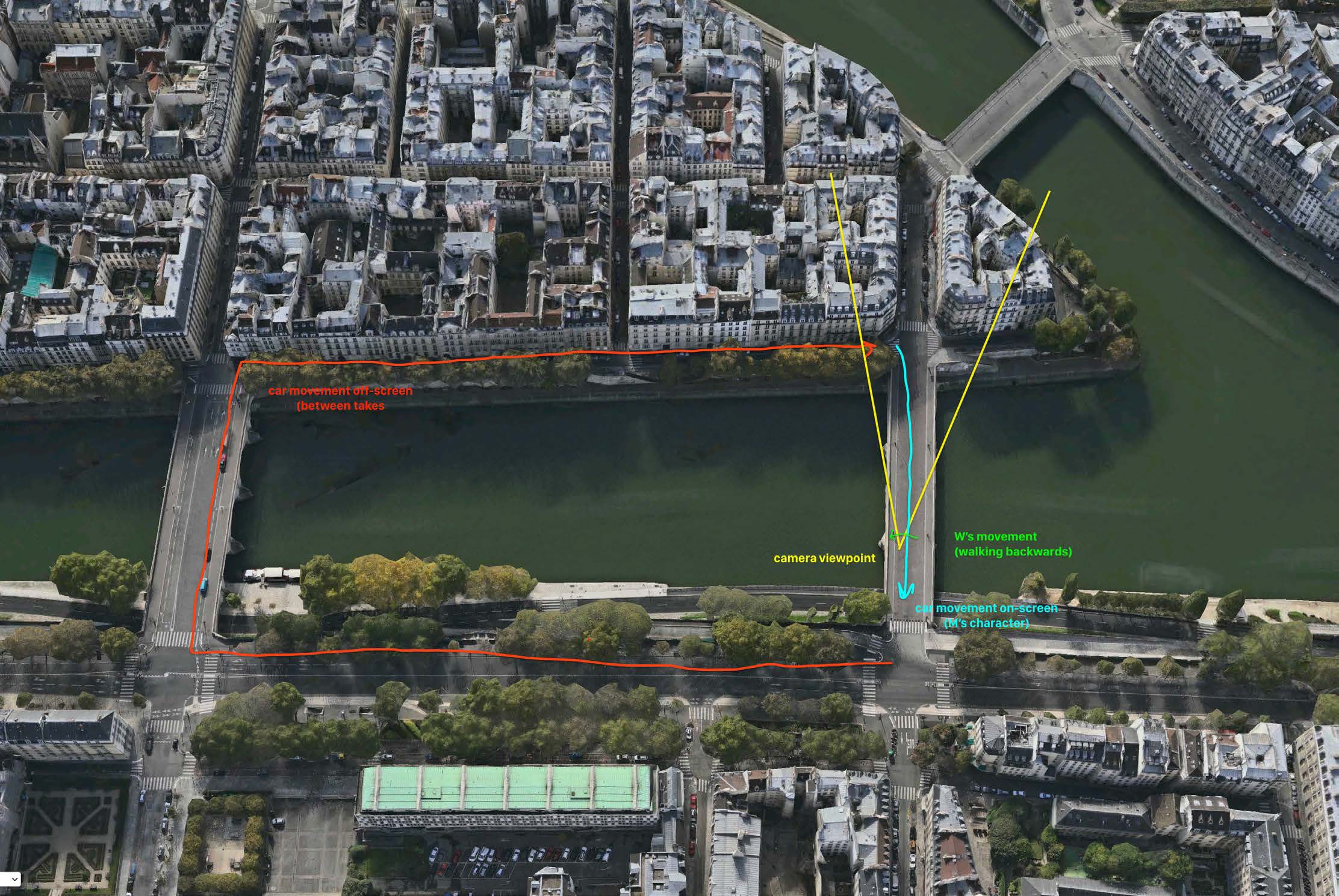

Much of M's routine involves travel in the back of a car. This meant that I had to have several shots of 4-20 seconds' length of M in a car. The camera would be positioned low down, between the two front seats, facing up at M, who would be seated in the centre of the rear seat. The budget of the film would not allow for executive car hire, so I used Uber Executive (a taxi service providing executive cars) for a journey from the Palais de Tokyo to Pont Louis Philippe bridge. I spent time in advance searching for a journey that would feature tunnels similar to those I had seen on Google Street View of Seoul; this journey ensured that the driver would take the express road by the river that was also away from the distinctly Parisian buildings we would pass (the low camera angle would also mask our true location). This journey would also take us to the bridge where the intersection shot could be filmed (the actor playing W, plus the two assistants followed us in a second Uber Executive taxi, which we would use to shoot the transition shot, around 25 minutes later).34

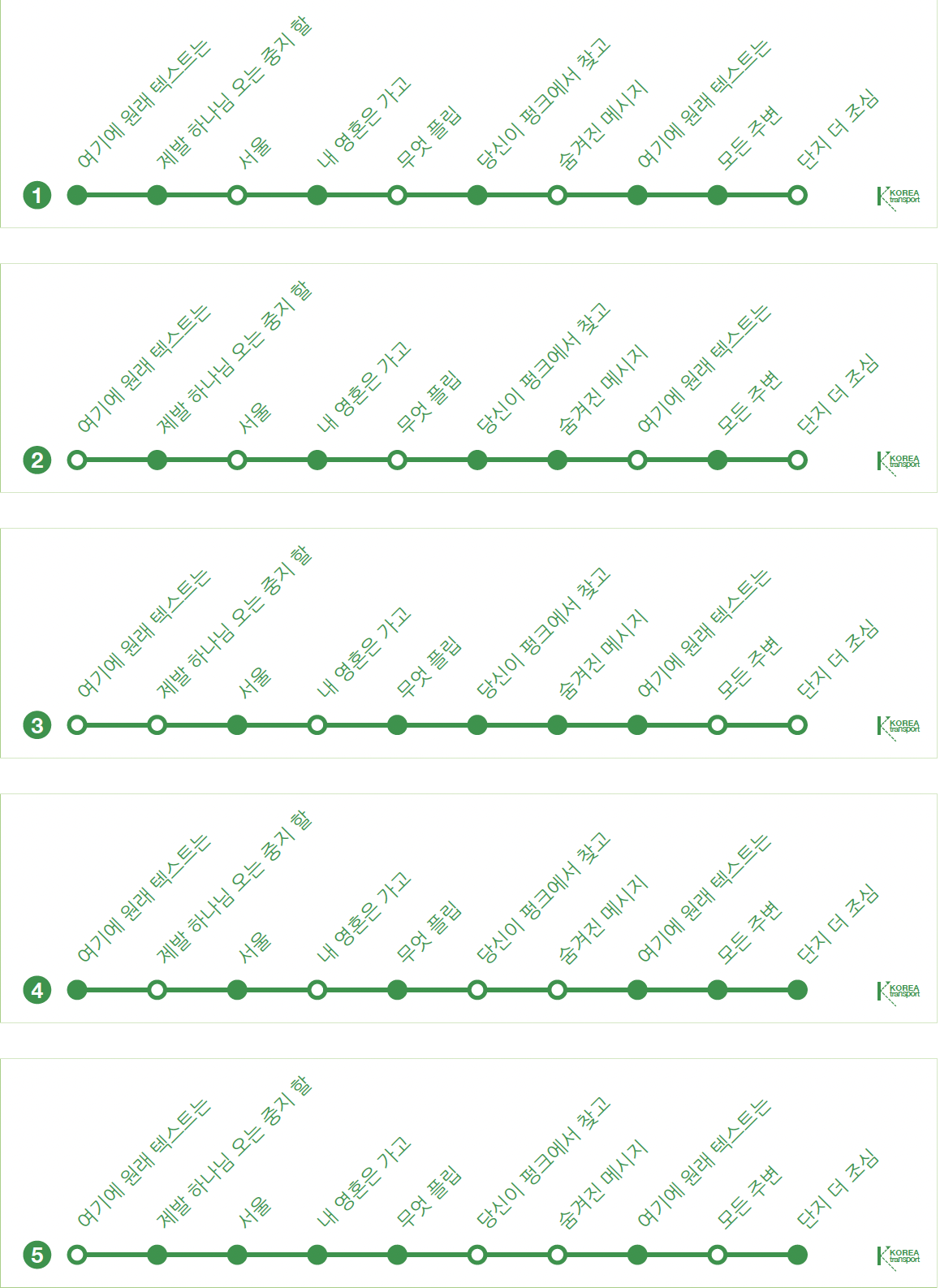

Unlike M, W's character is a low-level employee, ill-compensated for their work, travelling by crowded public transport to a shoddy, generic office with a temporary for a gruelling 12-hour shift.35 The buildings he inhabits would be generic, slightly run-down; I also wanted to include a Kaufman-esque office that would deteriorate in reflection of the characters' identity breakdown. The shots of W travelling to work would be shot on the Paris Metro system, but with masks similar to the ones the IRA used on their ‘Atlanta Airport’ truck to disguise it. The Parisian Metro is particularly visually distinctive, with many trains having doors which require manual opening, as well as a number of 'themed' stations.36 I chose to film on Line 1, whose relatively modern trains (and their doors) are automated, and whose interiors featured long illuminated panels onto which fake Korean subway maps could be attached.37

I designed four sets of maps, which originally were intended to feature in four scenes of the film (however, in later editing this was reduced to one map). The station names, written in Korean, were in fact partial sentences taken from Moore’s Diagramming Control, and translated into Korean using Google Translate. All of the shots on the Paris Metro would be taken with a short-focus lens, and feature a close-up of the ‘Korean’ Metro map, followed by a pan to W's character arriving in a station, then following him as he leaves the train and turns right to walk down the platform. Whilst filming, we would then both run to get back onto the train, re-entering in a loop so that we could film the next scene at the next station without losing the map.

Another part of the Parisian Metro to feature heavily in the film was Châtalet des Halles station. When I had first moved to Paris, I had taken note of Châtalet's long travellator.38 It was as notable for its length (around 300 metres) as well as its unusual form; a horizontal section with a high ceiling is contrasted halfway along with a curved incline and a low ceiling. During the time I was resident in Paris, Châtalet was also being refurbished, and the travellator had a series of exposed beams above it: the unnaturally steady movement of a camera on the travellator combined with the exposed building innards would make a perfect texture for a film about a person who is experiencing a sense of detachment from their surroundings. The same short-focus lens was used as for the Metro train shots, and green, municipal-style posters were stuck to the side of the travellator every 10 metres or so that said ‘Remember: You're in Korea’. I liked this idea because it was so absurd; I have never seen a poster to remind an audience which country they're in. In the film, W's character looks at the poster at exactly the moment his voiceover dialogue says “How can we trust anything when solidity itself is an illusion?” The posters can also be seen in the corridor of W's office building as he enters every morning.

The travelator served the modular filming method well; we would film W's character in one costume travelling both ways on the escalator, and upon return to the original end (where our assistant was waiting with the equipment bag) W would change into another costume, and we would loop again. Our other assistant waited at the other end of the escalator to look out for officials. We shot every variant of W’s multi-costumed character in both directions on the escalator.

Transition shots#

I needed to devise a means for the characters to pass on the chaotic ending of their story to the gentler beginnings of the other story. The beginning of W's story would focus on an atom spinning, and W’s justification for their work: that ‘there is so little matter in the universe, it may as well not exist’ (and therefore that reality is but an illusion, and a little more untruth is no different). I found this ‘fact’ through an IRA-derived process: Googling terms such as ‘nature of reality’ or ‘amount of matter in the universe’ until I found websites (of questionable quality) that presented me with information that suited the characters’ motivation. The model ‘atom’ used in W’s film was a wine cork placed onto the end of an electric drill's screwdriver head. The drill used had a built-in LED light which activated when the drill operated; thus, the drill itself provided both the atoms' spinning and illumination. This scene would be the counterpoint to M's identity breakdown, which would present M repeating a palindromic series of lines as if a spinning kaleidoscope (an effect generated in post-production).

The other ‘transitional’ scene would take advantage of the physical positioning of the screens within the film; using two identical cameras placed on a special rig, I would film the characters' paths crossing in a city. The moment would be an intersection of two paths, as in the title of Calvino's chapter. At the height of W’s breakdown of identity, M would pass in a car, pause as if at traffic lights; M and W would look at each other, and M’s car would continue. This would establish a power relationship between the two characters: M’s travel by executive car would contrast the busy, confused journey by metro we had just witnessed W taking, thus establishing M as a person who is in control. At the same time on-screen an audio cue would direct attention to the other screen: the stereo track, which during W’s film playing forward would be entirely on the left (where W's film is) would transfer to the right (where M’s film is). The shot would require technical logistics and another diagram.

A site was chosen on a bridge in Paris for the live-action transition – Pont Louis Philippe.39 I had lived near to this bridge, at the Cité Internationale des Arts artist studios for 3 months, and had observed the bridge and its footfall near-daily. The one-way bridge is uniquely placed in Paris, as it is adjacent to another, far busier bi-directional bridge (Pont Marie), yet itself has very small vehicular throughput. The high number of one-way streets in Paris were a consistent consideration for film-making. This particular layout, and the relatively quiet nature of the location, meant that between takes the driver could do a loop of the nearby streets to 'reset' the shot each time (see Figure 4-45), as well as ensuring that the actor playing W could safely stand in the middle of the road (supervised by assistant Justine Hermant) between shots.

The shot was planned via a diagram; the basic premise was that two identical BlackMagic Pocket cameras would be placed next to each other on a rig, so that the right edge of the left camera’s frame would line up with the left edge of the right camera, thus creating an extremely wide-angle shot (the 32:9 ratio with 3880x1080 pixels). W and M would be framed on their relative sides of the screen, save for the time when W crosses the screen into M’s shot. W leaving his own screen was a deliberate choice; I wanted the audience to have a visual cue as to which screen they should divert their attention to. Figure 4-47 shows the actions that had to be performed for this to take place; shooting two films at once, one would have to be reversed. W’s film was the only logical solution, as this shot comes at the end of his film, as part of his confused state (so the rest of the world working the other way round from him makes sense) and M, being composed and in control at the beginning of his film, would have to be moving forwards. The solution was to film W’s end-scene backwards, and M’s introduction scene forwards, both at the same time. Therefore W would walk backwards from right to left of the screen as M’s car approached, then pause and look at M, then walk backwards off-camera to the left as M’s car drove away to the right of the screen. The audience would see the entire scene backwards the first time around, so that W walks up to a car that is reversing up the street, looks at M, and then crosses the road as M reverses out of view, then as both films change direction, W would be walking backwards whilst M moves forwards.40

This day of shooting took a deal of logistical planning: it was the only day that both actors could schedule to work together. I met with M and W, and assistants Justine Hermant (JH) and Justine Emard (JE) at the Palais de Tokyo in the morning. I explained the logistics of each shot that we had to get that day, and we used the Pavillon studio and an unoccupied exhibition space to practise the shots. We then split into two groups: M and I would take an Uber Executive through Paris on the route that enabled us to film his in-car shots. M, JH and JE would follow in another Uber Executive 25 minutes later, and we would all rendezvous at the bridge, where we would shoot the transition scene. M would then leave, and W, the assistants and myself would go to the Cité Internationale des Arts to shoot all of W's corridoor scenes.

Audio#

A crucial technique in the signalling of screen the audience should focus on (besides the obvious film direction) would be the audio track. Having two films playing side-by-side in the opposite direction to each other, I wanted a method to ensure the audience knew where to look. Using stereo sound, the audio of the film that is playing forwards is selected to come from that side of the screen, so that when W’s film is playing forwards – on the left screen – the audio is active in the left channel and silent in the right, and vice versa for M. The transitional scenes, where one storyline transitions into the other, and the direction of both films changes, would feature a cross-fade to signal this change. In the video shown in Korea, subtitles would also act as a visual cue.

Audio also became a crucial part of the editing process. I always find editing a film sequence to audio far easier than editing without. This film was edited on non-linear editing software Premiere Pro.41 In the software, it is possible to place visual markers, say, every 4 seconds, which can be used to trim clips as needed. But this does not always aid the pace of film-editing; so I decided to use a click-track equivalent. Using the programming language Processing and sound library Minim, I generated two sine-wave notes (C5 and G5) of 0.5 seconds’ length.42 These were imported into the timelines of the two films, M and W, in my Premiere Pro timeline so that every second a note would play – a G every fourth second, and a C every other second. This meant that I was able to remain conscious of pacing and timing of shots whilst editing. As every cut would fall on a G, it became easy to work out how long shots I was editing would last, and whether they were suitable. It is remarkably hard to edit shots to a particular length without such a click-track. In the final edits of the films, I decided to keep the click-tracks in; their consistency led to a distinctive aesthetic, similar to that found in Nybble, and helped signal the audio cue from one screen to another, and their pacing gave a sense of order. It also proved to be an interesting artefact of the process that had led to the films; an instance of the form being shaped by the content.

Visualising break-down#

During W's film, the audience witness him creating false stories similar to those that Chen describes: mundane mis-truths about small towns in the American coutryside. I wanted the towns to sound distinctly American and plausible, so downloaded a dataset of small towns in the United States from the US Government's Open Data site.43 In my trips to the United States over the past few years, I had been struck by the distinctive way in which Americans say town names – normally, the town's name is closely followed by the state it is in. This seemed like the sort of detail that the IRA would have picked up on. W's dialogue when describing fictional events would be like a news ticker:

Swink, Oklahoma. The senator's wife still missing. Temecula, California. A plane crash...

However, the town names become more confused:

Agora Hills, California. A strange man in a trench coat. Agnosia Hills, California…

Agora Hills is immediately followed by Agnosia Hills. Agnosia is a mental symptom whereby the subject fails to recognise or identify objects, often associated with conditions where patients lose their grasp on reality (e.g. Altzheimer's).44 W's statements become more confused and mundane as the film goes on, eventually culminating in the statement:

Seoul, South Korea. A businessman in a car.

This signals something he is actually seeing: therefore, the false worlds he creates and the one he lives in are merging. W falls victim to his own trap, believing the untruths he spreads whilst add another layer to his uncertain reality.

The short, succinct style for these lines had several influences. One was my memory of news-ticker headlines from old radio programmes when I was a child. Another was Dora Garcia’s book All the Stories, which is a compendium of short stories with many sources, each told in a few sentences;45 another still was the opening to Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour programme, which ran from 2006-2009. At the beginning of each episode, a female voice declared a series of short statements in a consistent format:

It’s night time in the big city. A truck driver runs a red light. A strange quiet man practices tai chi in a park. It’s Theme Time Radio Hour with your host Bob Dylan.46

The statements were short and intriguing, with just enough detail to paint an intriguing picture of a scene.

Another signifier of the chaos in W’s life is his office cubicle: it becomes messier as he becomes more confused. All of the scenes featuring W at his desk were in fact shot with a forced perspective – and angled table – against a rear-projection screen.47 This was the same rear-projection set also used for M's office scenes. W's office cubicle was a model built of polystyrene board, built with Justine Emard. With a fixed-position camera, we shot video of the scene becoming messier over time; the carpet gets patchy and stained, post-it notes, documents and maps get stuck onto the wall, and the floor becomes covered in messy paper and rubbish.

The office’s exterior also changes over time. The shots of W walking down the corridor were shot at the Cité Internationale des Arts, and feature the same ‘Remember: You're in Korea’ posters as the travellator scenes on the metro. The company W works for is called Ray Inversion (a reference to M’s character). Each time M enters the door, the sign is increasingly distorted (reflecting the ever-changing, temporary offices Chen describes and W's mental state):48 first, the sign is shabbily taped to the door; then taped upside down; then, multiple signs are taped haphazardly on top of each other. The external world again reflects W's current state of mind.

Similarly to W’s office, M’s board-room was also a model with a forced perspective. However, the process was slightly different for M: first, footage of M (and myself, as the ‘client’) was shot on the same set as W’s cubicle (the rear projection screen). The image projected behind M is a blue wallpaper pattern that was ‘mirrored’ in Photoshop to create a line of symmetry. We shot all of M's scenes, including the scenes featuring me as M, and recorded the dialogue digetically. These scenes were then edited for visual clarity (increasing contrast, eliminating unwanted background, etc.) and the footage transferred to an 27" iMac with high-resolution screen. The iMac itself was placed into a forced-perspective model of M's boardroom, and each scene re-shot from multiple angles, so that it appeared that M was inhabiting a miniature model.

The paperwork that M is seen looking at in his office are stylised re-drawings of diagrams taken from an ebook copy of Newton's Opticks.49 These were printed on top of discarded corporate spreadsheets, salvaged from a bin in Paris. The table under the paper gains the superimposition of Prelinger Archive footage of a giant telescope, further highlighting the visual metaphor.50 This optical metaphor also spread into the buildings that M inhabits: these were simple models constructed from elements of Flickr images of downtown Seoul (a technique inspired by the IRA). The images were mirrored to echo the central motif of M's story; this image was then put onto a high-resolution TV screen which was placed behind cardboard cut-outs of mirrored buildings taken from other images of buildings in downtown Seoul. These buildings also featured the logo of an eye – designed to be one of M’s company logos. The design of this logo was based around Ptolemy's idea that vision occurs via the eye casting out beams of light;51 the logic being that the protagonist in Calvino’s story begins by paraphrasing Plotnius, and therefore would be likely to have also read early treatise on vision by other Greek philosophers.52 I did design logos for companies that would serve as a basic visual history of optical theories throughout philosophy, but cut the detail before shooting as it was a concept too complex to explain via the script.

Performance reflecting propagandist techniques#

The mode of performance for the actors was designed to reflect the IRA techniques. As the IRA workers are given the minimum information required to carry out each task – often resulting in them sending confused, contradictory messages – the actors in this film were deliberately given minimal instructions in order to act in each scene (with the exception of the bridge-transition scene).53 This was a mode of answering the research question, extending scripting to the process of producing a film, and often led to absurd scenarios.

For the break-down of M’s character, I wanted to evoke a feeling of lack of meaning to the words the actor was speaking. This would create a sense of confusion, similar to the confusion the character M was supposed to be feeling at that time (I had thought of his mental state as being like Fregoli delusion, whereby facial recognition and the boundaries between self and others are warped).54 In order to evoke this state, the actor would be directed to repeat the palindromic script, which also featured numerous optical references (‘shift the focus’), until it lost all meaning, getting faster and louder each time. Since I played the ‘other’ that M merges with, I also underwent this process. After about 2 minutes, I entered a trance-like state of repetition, and the script I had written was unrecognisable. However, this is one area of the film that I do not feel is successful; it is a repeated palindrome within a repeating palindromic film, but the audio recording was low quality.

Similarly, whilst shooting W as his multitude of characters, a ‘modular’ approach was taken. This involved a rotating array of rear-projected backgrounds (the disintegrating office scenes), a repeated set of instructions, and a series of costume changes. The idea was to get footage of every permutation of W's character, against every possible background, behaving in one of four manners (staring vacantly at the camera, typing, typing manically and ‘freestyle’), so that this footage could be interspersed later on in the editing process. Shooting these scenes took around 4 hours, during which time the actor repeated the same behaviours hundreds of times. It became a strange, ritualistic performance, and, like shooting M’s character, during shooting the ritual overtook any sense of meaning.

-

Felix Barrett and Maxine Doyle, The Drowned Man: A Hollywood Fable, Play (Temple Studios, 31 London St, London W2 1DJ, United Kingdom: Punchdrunk and the National Theatre, 2013). ↩

-

G. Bateson, ‘A Theory of Play and Fantasy’, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 13. printing. (Ballantine, 1985), 193. ↩

-

Among other things, I also admired the highly rigid structure the play had used to choreograph people to move through a space; despite seeing the play multiple times, I had not noticed the consistent increments of time. ↩

-

Italo Calvino, ‘In a Network of Lines That Intersect’, in If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, trans. William Weaver, Array (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981), 157–64. ↩

-

Ibid., 158. ↩

-

Hebe George and Maito Jobbe Duval, ‘Punchdrunk Design Masterclass’ (Temple Studios, 31 London St, London W2 1DJ, United Kingdom, 16 June 2014). ↩

-

1813-1837 Büchner Georg, Woyzeck, ed. Nicholas Rudall, Plays for Performance (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002); Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (New York: The New Classics, 1950); George and Duval, ‘Punchdrunk Design Masterclass’. ↩

-

Note that research for this project began in 2015, and was completed in April 2016, before the major political events of that year unfolded, and the term ‘fake news’ gained popularity. ↩

-

Adrian Chen, ‘The Agency’, The New York Times, 2 June 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/magazine/the-agency.html. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Peter Pomerantsev, ‘Inside the Kremlin’s Hall of Mirrors’, The Guardian, 9 April 2015, Online edition, sec. The Long Read, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2015/apr/09/kremlin-hall-of-mirrors-military-information-psychology. ↩

-

Quoting Information-Psychological War Operations: A Short Encyclopaedia and Reference Guide, Ibid. ↩

-

This phenomenon has received significant news coverage in light of allegations following recent political events in the US, UK, and France. See, for example, Farhad Manjoo, ‘As Internet Seizes News, Grip on the Truth Loosens’, New York Times, 3 November 2016, National edition, sec. Business; Carole Cadwalladr, ‘The Great British Brexit Robbery: How Our Democracy Was Hijacked’, The Observer, 7 May 2017, sec. Technology, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy., among others. ↩

-

Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October 59 (1992): 3–7; Nathan Moore, ‘Diagramming Control’, in Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity, ed. Peg Rawes, 1st ed. (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013), 56–70. ↩

-

Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, 4. ↩

-

Moore holds an MA in Architectural History from the Bartlett. ↩

-

Max Colson and Ollie Palmer, ‘Exploring Virtual Control Workshop’ (Stratford Station, Westfield Shopping Centre and Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, 18 August 2015). ↩

-

Anna Minton, Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century City, 1st ed. (London: Penguin Books, 2012), 44. Minton writes extensively about ‘private-public partnerships’, describing them as ‘pseudo-private space’. Ibid. ↩

-

Nathan Moore to Ollie Palmer and Max Colson, ‘Westfield and Olympic Park’, 21 August 2015; Ollie Palmer to Nathan Moore and Max Colson, ‘Re: Westfield and Olympic Park’, 21 August 2015. ↩

-

‘Reflexive, Adj. and N.’, OED Online (Oxford University Press), fig. 2d, accessed 8 May 2017, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/160948. ↩

-

Ibid., fig. 2c. ↩

-

This led to the film's dimensions being 3880 x 1080, or a 32:9 ratio. ↩

-

Chen, ‘The Agency’. ↩

-

Chen discusses the 12-hour days, the seemingly temporary nature of the offices, and the routine of the workers in detail. ↩

-

In Eternal Sunshine for the Spotless Mind, the revolutionary new technology which enables selective wiping of memories has been adopted by a doctor who runs a chaotic office akin to a low-budget plastic surgery in suburban America. Michel Gondry, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Drama, Romance, Sci-Fi, (2004). ↩

-

The idea of a dual-screen film that plays forwards and backwards has previously been used by Michel Gondry in the music video for Cibo Matto's Sugar Water. The music video features a split screen showing the two members of the band, with the left half of the screen playing forwards and right backwards, and horizontally mirrored. Half way through the video it becomes apparent that the entire film was in fact shot on one camera; the focus of the left screen changes from singer 1 to singer 2; which of course means that in the mirrored video, singer 2 is replaced by singer 1. The video is technically highly sophisticated in its form, and ability to synchronise the actions of characters at nearly all times. It contains a number of interesting filmmaking techniques. Michel Gondry, Sugar Water, Music video (Warner Music, 1996). ↩

-

See Manuel De Landa, Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 33. De Landa quotes Gilles Deleuze and Paul Patton, Difference and repetition (London; New York: Continuum, 2001), 208–9. “The virtual is fully real in so far as it is virtual” ↩

-

Max Coltheart, ‘Delusional Belief’, Australian Journal of Psychology 57, no. 2 (August 2005): 72, doi:10.1080/00049530500125082. ↩

-

Computers use a base-2 system because information is stored in binary 'bits' (1 or 0). ↩

-

My personal laptop was the most practical computer to use, since I could use it anywhere, and it would be guaranteed to journey to Korea with me during the final phase of the project. I imagine that in the future, much film editing software will rely on cloud-based solutions, and rendering relatively simple footage such as mine will be far faster. However, this film was made in 2016 on a 15" MacBook Pro. ↩

-

I advertised and cast gender-blind for both roles; however, from the applicants, the two actors best suited to the roles were both male. ↩

-

Alexander Rodchenko, The Stairs, Photograph, gelatin silver print, 1929, https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/2000.87. ↩

-

Pont Louis Philippe was also very close to the Cité internationale des Arts, where my live-work studio was located. ↩

-

Chen discusses these long schedules, and describes the routine of the workers' entry and exit to their building. ↩

-

The station at Musee de Arts and Metiers, for example, is themed after Jules Vernes' Journey to the Centre of the Earth, with riveted copper throughout the platforms. ↩

-

The fully automated trains also appeared less likely to be patrolled by officials who may not have approved of our unauthorised filming. ↩

-

Châtalet les Halles was the first station I had to transfer at on arrival in Paris, encumbered by large bags full of equipment for studio production. ↩

-

This was also the end-location for M's driving shot. ↩

-

I had calculated the camera rig dimensions through my earlier measurements of camera angles. However, on the day of shooting, there was an error with one of the BlackMagic cameras, so I had to create a similar rig for two Canon cameras and a pair of tripods at the last minute; the mis-alignation can be seen in the final film. ↩

-

Adobe Systems Incorporated, Premiere Pro, version CC 2015.2, Mac OS X (Adobe Systems Incorporated, 2016). One feature of my workflow that evolved, rather than being planned, was a result of the high internet speed I had access to whilst editing in Korea. The studio I worked from (at SeMA’s Nanji artist residency) had an internet connection with over 100 Megabyte per second upload speeds. When editing films, I usually ask someone else to review my timelines – in most instances, this is a colleague who is not involved directly with the project. In Nanji, I consulted Abi Palmer (see also Nybble in chapter 2); she was based in London. I was editing the film at night, exporting sections of film from Premiere Pro, uploading clips as private videos to YouTube, and sending her links to the videos. The process was highly efficient. In a number of instances, I made edits we discussed whilst on the phone, and was able to show her the result in a number of seconds. ↩

-

Processing Foundation, Processing 2.2.1, version 2.2.1, Mac OS X (Processing Foundation, 2014), http://www.processing.org. ↩

-

US Census Bureau Creating office name here, ‘Incorporations, Mergers, Consolidations and Disincorporations’ (United States Census Bureau), accessed 8 May 2017, https://www.census.gov/geo/partnerships/bas/bas_newannex.html. ↩

-

The term ‘agnosia’ was coined by Freud, and possibly popularised by Oliver Sachs in The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat: And Other Clinical Tales (Simon & Schuster, 1998). See also American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), Fourth Edition, Text Revision (Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association, 2000), 152; Hillary R. Rodman, ‘Face Recognition’, in The Mit Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, ed. Robert Andrew Wilson and Frank C. Keil (MIT Press, 2001), 309–11. ↩

-

García's stories appear to come from mutliple sources: original stories, guest contributions and synopses of popular works. Examples include: ‘A man designs a switch that will let him live or will make him die. He spends the rest of his life staring at the switch.’ and ‘In the year 2001, an expedition discovers a hostile alien brain who can turn thoughts into reality.’ (The latter quote obviously the synopsis of 2001: A Space Odyssey). Dora García and Book Works (Organization), All the Stories (London; Birmingham: Book Works ; Eastside Projects, 2011). Note: the book has no page numbers. ↩

-

Bob Dylan, ‘Episode 6: Jail’, Theme Time Radio Hour Archive (XM Radio, 7 June 2006), http://www.themetimeradio.com/episode-6-jail/. ↩

-

I built the rear projection screen in the Pavillon studio on a budget of €40 from two Muji shower curtains taped together, placed in front of a projector. The filming had to occur after dark thanks to the low light output of the projector; the set was designed so that both M and W's characters would have matching desk positions, and made use of the earlier camera setup diagrams I had created. ↩

-

Chen, ‘The Agency’. ↩

-

Sir Isaac Newton, ‘Opticks: Or, A Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light’ (Project Gutenburg, 23 August 1730), http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33504. ↩

-

Aura Productions, Journey Into Light, 1973, http://archive.org/details/6238_Journey_Into_Light_01_29_44_29. ↩

-

A. Mark Smith, ‘Ptolemy’s Theory of Visual Perception: An English Translation of the “Optics” with Introduction and Commentary’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 86, no. 2 (1996): 246, doi:10.2307/3231951. ↩

-

Calvino, ‘In a Network of Lines That Intersect’, 157. ↩

-

Chen, ‘The Agency’. ↩

-

See Max Coltheart, ‘Delusional Belief’, Australian Journal of Psychology 57, no. 2 (August 2005): 72–76, doi:10.1080/00049530500125082; William Hirstein, Brain Fiction : Self-Deception and the Riddle of Confabulation., Philosophical Psychopathology (MIT Press, 2005), 116; Todd E. Feinberg et al., ‘Multiple Fregoli Delusions after Traumatic Brain Injury’, Cortex 35, no. 3 (1999): 373–87, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70806-2. ↩