Chapter 1: Diagramming the Absurd#

The Godot Machine and Ant Ballet

Overview#

The contexts in which artworks are exhibited frame the way in which they will be interpreted by an audience. This chapter presents two projects (Ant Ballet and the Godot Machine) initiated during Masters degree study, and subsequently exhibited in and modified for different contexts, including those associated with 'sci-art'. Ant Ballet represents a novel approach to scripting animal behaviour; The Godot Machine represents the application of a robust diagramming design methodology to an absurd project. The chapter re-frames the projects from their previous sci-art position to state their original intention as modes of diagramming the absurd and as explorations of notions of script. The re-framing of these projects enabled a critical reappraisal of their content and the development of the methodology used for later projects in this thesis, as well as some criteria for project assessment.

Project videos#

Ant Ballet: videos

Ant Ballet: project video

Video included for reference only. Project does not form part of portfolio submission.

Ant Ballet: BBC News article

Ant Ballet as exhibited at FutureEverything Festival, Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester in 2012. BBC News report by Dougal Shaw, © BBC News 2012.

Introduction#

This chapter addresses the diagramming and framing processes that underpin my design practice. It draws upon Gregory Bateson’s Theory of Play and Fantasy, and Barry and Born’s work in defining sci-art practice, and refers to two projects: Ant Ballet and the Godot Machine. These projects were initiated before the start of my PhD (with iterations of both forming part of my MArch portfolio) but continued into the first year of doctoral research, and were central to the development of later work.1 In particular, it was in the production of these pieces that diagramming first entered my practice, with both works taking the form of machines that manifested specific diagrammatic systems.

It should be noted that the Godot Machine and Ant Ballet are used here purposes of reference only, and not as part of my thesis portfolio (this is clarified by appendicising all technical information for both projects). In addition to the methodological role they play, these works represent and define a major shift in the framing of my work away from the ‘sci-art’ genre.2 As such, I use them here as a basis for the critique of that field, and the platform upon which to build a more theoretically robust definition of my practice. This chapter focuses on the re-establishing the intention behind these works, defining the framing and diagramming processes that emerged from them, and assessing their implications for other projects in this thesis. As an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded PhD has a responsibility to discuss methods and processes involved in the creation of work, I see these works as essential reference points for the thesis, acting as a catalyst for future projects, and also as a framing device for subsequent chapters. These projects have also played an important role in opening up my design work into an artistic context, as it was on the basis of Ant Ballet (as exhibited at FutureEverything festival in Manchester) that I was offered the residency at the Palais de Tokyo, thereby also redefining the disciplinary scope of my practice.

Frames#

The conceptual frame in which a piece of art exists is central to an audiences’ understanding of it. The British cyberneticist Gregory Bateson wrote extensively about the relationship between the way humans mentally construct the world they inhabit and the way they perceive and create cultural phenomena, such as artwork. How do we know to treat art as art, or to separate the fiction in a story from everyday lived experience? Is this ability to separate the fictitious or fantastical from the real an innately human quality, or can it be seen in other animals? And what does this tell us about the way we see art? These questions are posed in Bateson’s essay A Theory of Play and Fantasy, in which he introduces the concept of mental frames.3

Bateson begins the essay with a vignette: while watching moneys play in San Francisco’s Fleischer Zoo, the author wonders how they are able to distinguish between play-fighting and real fighting and poses the question: how does this delineation happen and how is it communicated? Drawing on numerous disciplines, including anthropology, linguistics, semiotics, psychology and the study of animal behaviour, Bateson uses this example as a model to investigate the way in which humans conceptualise and analyse their experiences and thoughts in the real world and decipher meaning from communication.4 He begins by discussing language. Playing with another individual (as with two monkeys), requires an ability to communicate, but it also requires meta-communication: that is, communication about the communication. In the case of the play-fighting monkeys, the actions they perform clearly mimic the actions of combat, but somehow both monkeys know that this is play fighting, rather than real fighting. For example, the play bite symbolises a real bite, but does not elicit the consequences of the latter. Bateson therefore concludes that playing communicates a message: ‘these actions in which we engage do not denote what those actions for which they stand denote.’5 Bateson claims that this is similar to Alfred Korzybski’s famous argument about the relationship between the map and the territory it describes. Korzybski, a scholar in field of general semantics and linguistics, distinguished map and territory as distinct entities, arguing that a map is merely a model of the territory, and thus in being a model, the map becomes a simplified version of the territory:

A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure [^original emphasis] to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness. If the map could be ideally correct, it would include, in a reduced scale, the map of the map; the map of the map, of the map; and so on, endlessly [...].6

For Korzybski maps are an analogy for languages, which must ‘be considered only as maps [^original emphasis]. A word is not the object it represents’.7 When applied to Bateson’s monkey example, within the game, the monkeys’ play-bites act as signifiers of the bites they would do if it were a real fight. So within the monkeys’ play, the relationship between the actions they are performing and the actions they represent (i.e. play-fighting to real fighting) is akin to the map’s relationship to the territory it represents. The monkeys both know that this fight is a game, and some sort of communication is necessary to enable this to happen. The animals do ‘not quite mean what they are saying, but, also, they are usually communicating about something that does not exist.’8

Bateson argues that these games also occur in the human realm. In our appreciation of art (among other pursuits), for example, we too have to realise that we are indulging in a form of play, that the symbolic representations contained within the objects we’re looking at are mere representations:

At the human level, this leads to a vast variety of complications and inversions in the fields of play, fantasy, and art. Conjurers and painters of the trompe l'oeil school concentrate upon acquiring a virtuosity whose only reward is reached after the viewer detects that he has been deceived and is forced to smile or marvel at the skill of the deceiver. Hollywood film-makers spend millions of dollars to increase the realism of a shadow. Other artists, perhaps more realistically, insist that art be nonrepresentational; and poker players achieve a strange addictive realism by equating the chips for which they play with dollars. They still insist, however, that the loser accept his loss as part of the game.9

In play, the players must be reminded that they are playing. But play contains an internal paradox: there are messages within the message that tell the receiver that the action is play; in other words, that it is untrue. Play must be separated from the ‘real’ actions it symbolises. This process, Bateson argues, occurs through a ‘psychological frame’ and ‘context’.10

What, then, is a frame? Bateson claims that there are two examples that could be used to discuss the analogy: a picture frame, or a mathematical set. For the sake of clarity in this argument, I will only focus on the former. A psychological frame, like a picture frame, is a delimitation device: the frame around a painting marks the outer limits of the artwork, and ‘tells the viewer that he is not to use the same sort of thinking in interpreting the picture that he might use in interpreting the wallpaper outside the frame.’11 A similar, but non-physical device can be found in real-world scenarios where we have to ‘frame’ actions: jobs, plays, interviews and languages all require framing, insofar as behaviour inside these frames is understood to be distinct, and carry different symbolic meaning, to the actions that take place outside of it. A physical picture frame is itself an ‘excessively concrete’12 device representing an externalisation of our internal mental processes, since ‘human beings operate more easily in a universe where some of their psychological characteristics are externalised.’13

Psychological frames (and by extension, picture frames) are both inclusive and exclusive devices. Simultaneously, they act to include certain messages by excluding others, and exclude certain messages by including others. For example, a picture viewer asks the viewer to ‘attend to what is within and do not attend to what is outside.’14 Bateson continues:

The frame itself thus becomes a part of the premise system. Either, as in the case of the play frame, the frame is involved in the evaluation of the messages which it contains, or the frame merely assists the mind in understanding the contained messages by reminding the thinker that these messages are mutually relevant and the messages outside the frame may be ignored.15

The frame, then, is a ‘metacommunicative’ device;16 any message containing a frame ‘ipso facto gives the receiver instructions or aids in his attempt to understand the messages included within the frame.’17

Bateson’s psychological frame concept contains similarities with Schank and Abelson’s script theory.18 Schank and Abelson’s scripts are sets of rules which are activated when a person encounters a certain scenario; a number of these scenarios are examples of play (for example, football or squash). Although Schank and Abelson do not explicitly make the point, their concept of a scene requires a Batesonian frame, the imposition of which enables the triggering of scripts. The ability to play through imagined Schank-and-Abelsonian scripts in one’s head (such as imagining an encounter in a restaurant) could be seen as an example of Batesonian framing.

Within the world of artistic production, both psychological frames and script theory carry implications: the context within which work is presented, and even the genre the work fits into, much like a physical frame on a wall, delineates the limits and extent within which an artwork or project will be judged; and the script associated with the context – in other words the genre of work – delineates implicit and explicit rules, norms, and protocols, which are generally followed. Within the world of artistic production, defining the remit and scope of the virtual frame an artist works within is an important determinant of how their work is portrayed, understood and interpreted. Traditional Balinese painting, for example, will be interpreted according to different rules (or scripts) to a Van Gogh.19 Similarly, work displayed in the context of an art gallery will be interpreted differently to the same work presented in a science museum, by virtue of the psychological frame it uses and the scripted behaviour this elicits .

What relevance does an argument about psychological and knowledge frames have in this thesis? This chapter discusses two projects, which were instrumental in defining the scope and frame of the practice I now employ. Both of these projects worked with ants, with the aim of manipulating their behaviour, either as individuals or entire colonies. The development of these projects led to, and helped to shape initial research for this thesis; however, the original framing and exhibition of the Ant Ballet project as ‘sci-art’ (the meaning of which will be discussed shortly) placed undue emphasis on certain aspects of the project, which in turn undermined its absurd, diagrammatic intentions. This is discussed through a pair of exhibitions, one in which the work was exhibited in a scientific institution, and another where it was exhibited in the context of an art and technology festival.

Projects#

Godot Machine#

A central, famous, theme of the Samuel Beckett play Waiting for Godot is that ‘nothing happens, twice.’20 The play depicts two days in the lives of Vladimir and Estragon, which act as synecdoche for their entire existence; there is a sense of hopelessness to their every action, an inevitability to the repetition of events, a forgetting of incidents, places and names. The ‘controller’, the ever-absent Godot, is removed from the situation, leaving the audience feeling as though the characters are puppets, their strings being pulled from afar. It is a portrait of a pair of confused lives subject to abstract controls, with little sense of individual agency.

Similarly, there is a scene in George Lucas’ first feature film, the dystopic sci-fi thriller THX-1138, where the main protagonist wakes up to find that he is in a featureless, potentially infinite, white room, and that no matter which direction he walks in, he gets nowhere.21 Whilst the film as an entirety may be seen as a crude high-tech approximation of George Orwell’s 1984, and a continuation of the escape-from-dystopia plot consistently found in sci-fi, I found the image of the infinite void compelling when I first watched the film in 2009.22 The sense of despair and helplessness present in both the THX-1138 scene, and Waiting for Godot (as well as the image of Sisyphus in Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus) was something that I wanted to explore through a machinic diagram.23 Building a machine that would literally transport a person to a similar state as the aforementioned works of literature and film would not be logistically or financially possible. However, I was mesmerised by the emotional reaction I had to both of these works, and wanted to build something that evoked similar affect from an audience.

Engaging with fiction requires the viewer to enter a Batesonian frame; to knowingly realise that the fiction depicted on-screen or in the pages of a novel is fantasy. The same could be said of reading Foucault’s description of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a design for a prison (or high-surveillance education system), ultimately unrealised during Bentham’s lifetime.24 Foucault’s initial diagrammatic description of the Panopticon is as follows:

We know the principle on which it was based: at the periphery, an annular building; at the centre, a tower; this tower is pierced with wide windows that open onto the inner side of the ring; the peripheric building is divided into cells, each of which extends the whole width of the building; they have two windows, one on the inside, corresponding to the windows of the tower; the other, on the outside, allows the light to cross the cell from one end to the other. All that is needed, then, is to place a supervisor in a central tower and to shut up in each cell a madman, a patient, a condemned man, a worker or a schoolboy. By the effect of backlighting, one can observe from the tower, standing out precisely against the light, the small captive shadows in the cells of the periphery. They are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualised and constantly visible. The panoptic mechanism arranges spatial unities that make it possible to see constantly and to recognize immediately. In short, it reverses the principle of the dungeon; or rather of its three functions - to enclose, to deprive of light and to hide - It preserves only the first and eliminates the other two. Full lighting and the eye of a supervisor capture better than darkness, which ultimately protected. Visibility is a trap.25

In Foucault’s analysis, Bentham’s utilitarian diagram exists as a description, which we know is a work of invention. Yet the reader is able to empathise with the various characters, and even picture them residing in the building, via the disembodied frame they construct. The Panopticon then becomes a framed, hypothetical diagram of surveillance and control; it does not exist in the real moment of reading, but its virtual presence takes command. Foucault describes the prison functioning as a ‘kind of laboratory of power.’26 I argue that the real power of this hypothetical design lies in the readers’ tendency to construct the design within their own mind and subsequently project it onto themselves through a Batesonian frame. In the same way that Bateson uses Korzybski’s map-territory relation to differentiate between the actions of monkeys play-fighting and the actions that the play-fighting symbolise (i.e. real, violent fighting), there is a difference between reading Foucault’s description of the Panopticon as a model of power, and the functioning of a real-world Panopticon. In a similar fashion, my intention with the Godot Machine project was to construct a machine which functioned as a diagram, a visual representation of a power structure embodied in a medium that would be immediately and viscerally recognised, framed almost as a work of fiction.

The concept of the Godot Machine is simple: an ant sits atop a sphere. If it tries to walk forwards, the sphere rotated backwards. If it tries to walk to the right, the sphere rotates to the left. Irrespective of the ant’s attempts to move in any direction, it will always be mechanically rotated to return to the top of its own little world. In order for this to happen, the ant is monitored from above by a camera, which is connected to a computer control system and series of actuators under the sphere, which can in turn rotate it in any direction. The environment the ant is able to see is also carefully controlled, so that the ant can never visually orient itself with regards to the room that the machine is placed in. The project serves as a diagram of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (hence the project title): no matter what actions the ant takes, it cannot change its fate. This was the first diagrammatic project that I worked on, and a complete technical description of the project development can be found in the appendices.27

Ant Ballet#

Godot Machine was an absurdb machine in the most literal sense. The diagram of power relations was translated into an actual mechanical device, designed to provoke the realisation of the absurdb in the viewer. The project development was also relatively linear, whereby multiple versions of a design solution were prototyped, and the most effective solution was eventually chosen. Whilst working on the Godot Machine, I began developing a project entitled Ant Ballet, which explored the less tangible Deleuzian idea of the machine-as-system, via a more complex conceptualisation of the absurdb diagram.28 Godot Machine had analogised the central themes of the Theatre of the Absurd – namely loss of agency, disorientation and invisible power structures – via the manipulation of the individual ant.29 Ant Ballet aimed to take this idea one step further, by controlling a large group of ants by interfering with their internal communication system. Ants are commonly known to form and follow pheromone trails in order to find food.30 Since the early 1990s, the emergent behaviour demonstrated by this model of communication has fascinated computer scientists to the extent that it has frequently been used as a model for solving complex problems.31 Inspired by the almost computational logic built within this system, Ant Ballet project used artificial pheromones, made in a laboratory by organic chemists with whom I collaborated, to script the movement of a colony of ants. It did so via a machine that spread ant pheromones across a two-metre diameter ‘stage’ which acted as a literal theatre of absurd.32 Details regarding the technical and theoretical development of this project can be found in the appendices.

Much of the inspiration for Ant Ballet, and the consultation of scientific experts, was inspired by the film-making technique of Stanley Kubrick: in particular the film Dr. Strangelove (Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb).33 The film itself is a masterpiece of the absurd, featuring classically absurdist themes: the breakdown of communication systems, an entropic structure, and lack of individual agency.34 The film was released in 1964, around 15 months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, at a time when the threat of nuclear war was a very real possibility in the minds of many people, and focuses on exactly that subject. In the film, an errant US air-force base commander launches a nuclear attack on Russia which, through a series of mishaps and operational shortcomings, cannot be recalled. Over the course of the film, it is revealed that Russia has secretly built a ‘doomsday device’ which would trigger the country’s entire nuclear arsenal if any military sites are attacked. In a rare twist for a hit film, it culminates in the nuclear destruction of the world, but it is also full of dark humour. Much like the absurdist works, the actions of characters (and in this case the destruction of the world), are inevitable and unavoidable. It is both absurda and absurdb.

In the production of the film, Kubrick went to extreme lengths to ensure its technical accuracy. The depictions of numerous protocols, attitudes, and interiors have been deemed accurate by experts in the field.35 The story itself was developed from a novel by a former Royal Air Force flight lieutenant Peter George, following its personal recommendation to Kubrick by the head of the Institute of Strategic Studies in London, and throughout the making of the film Kubrick read over 50 books and consulted with twelve experts on the subject of thermonuclear war.36 The viability of the films’ plotline and characters accentuated the absurdb nature of the film itself, or rather, its proximity to reality heightened the potency of the absurdb realisation among the audience. In the creation of Ant Ballet, I aspired to similar levels of realism: if I were to make an absurdb statement, it would be one that was scientifically accurate. Where the Godot Machine employed engineering techniques, Ant Ballet required collaboration with scientists from different disciplines in order to work. Like Kubrick, the intention was not the accurate depiction of scientific realities onscreen, but rather using this medium to express an absurdb idea. Although the project depicted a real experiment, a real mechanism, real ants and their real reaction, it could equally be a work of fiction.

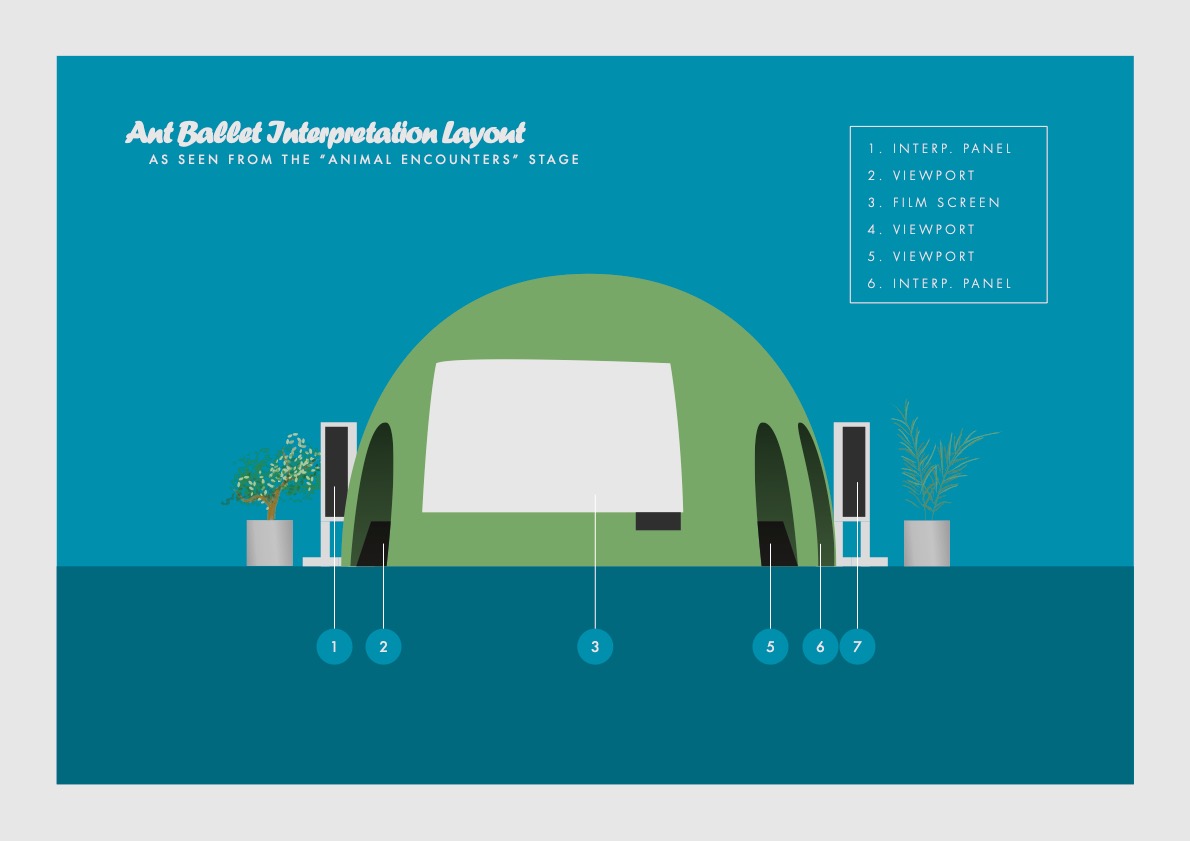

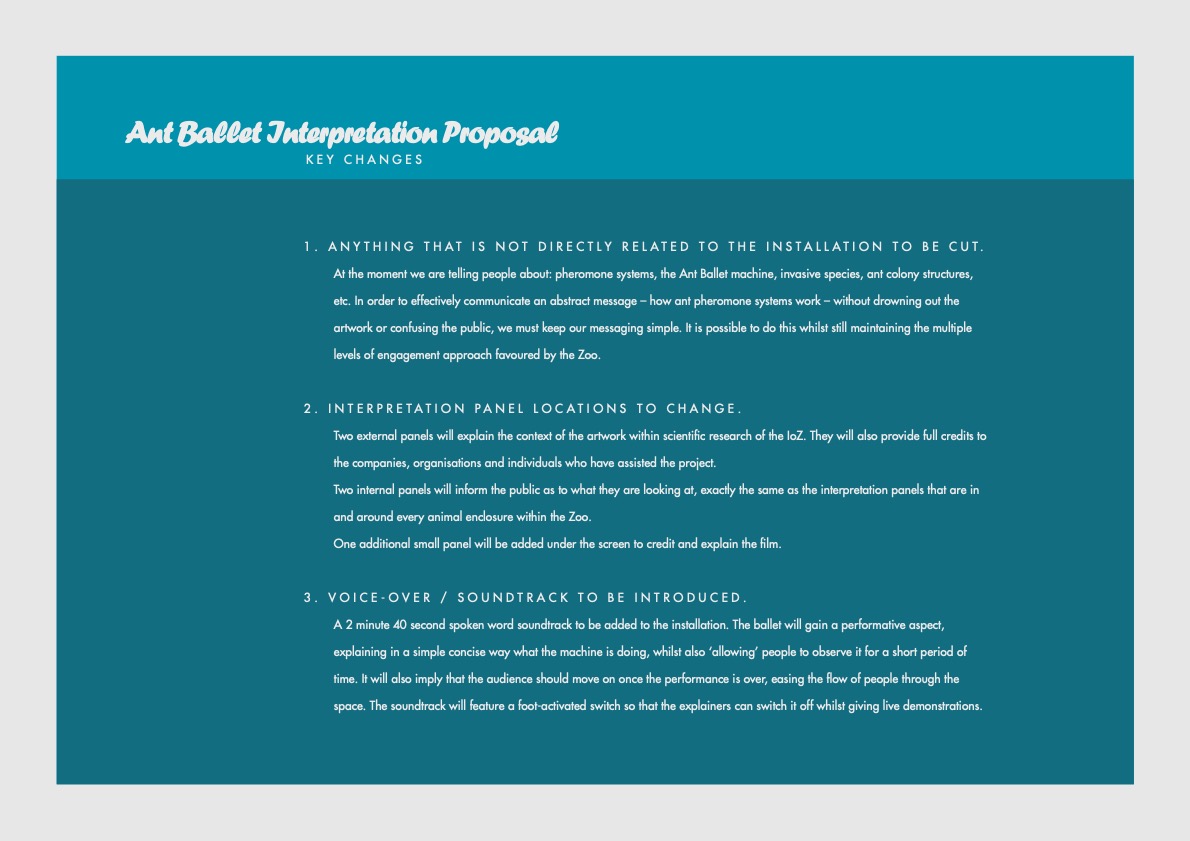

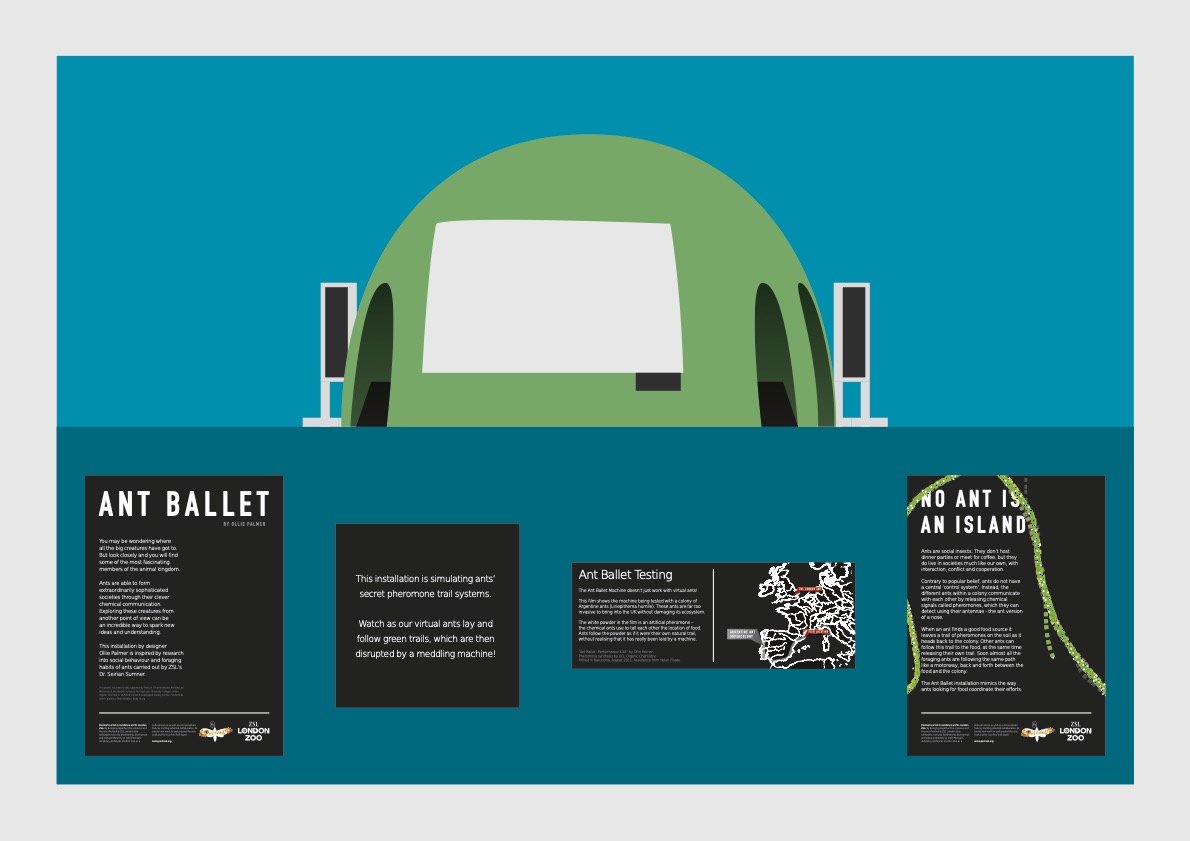

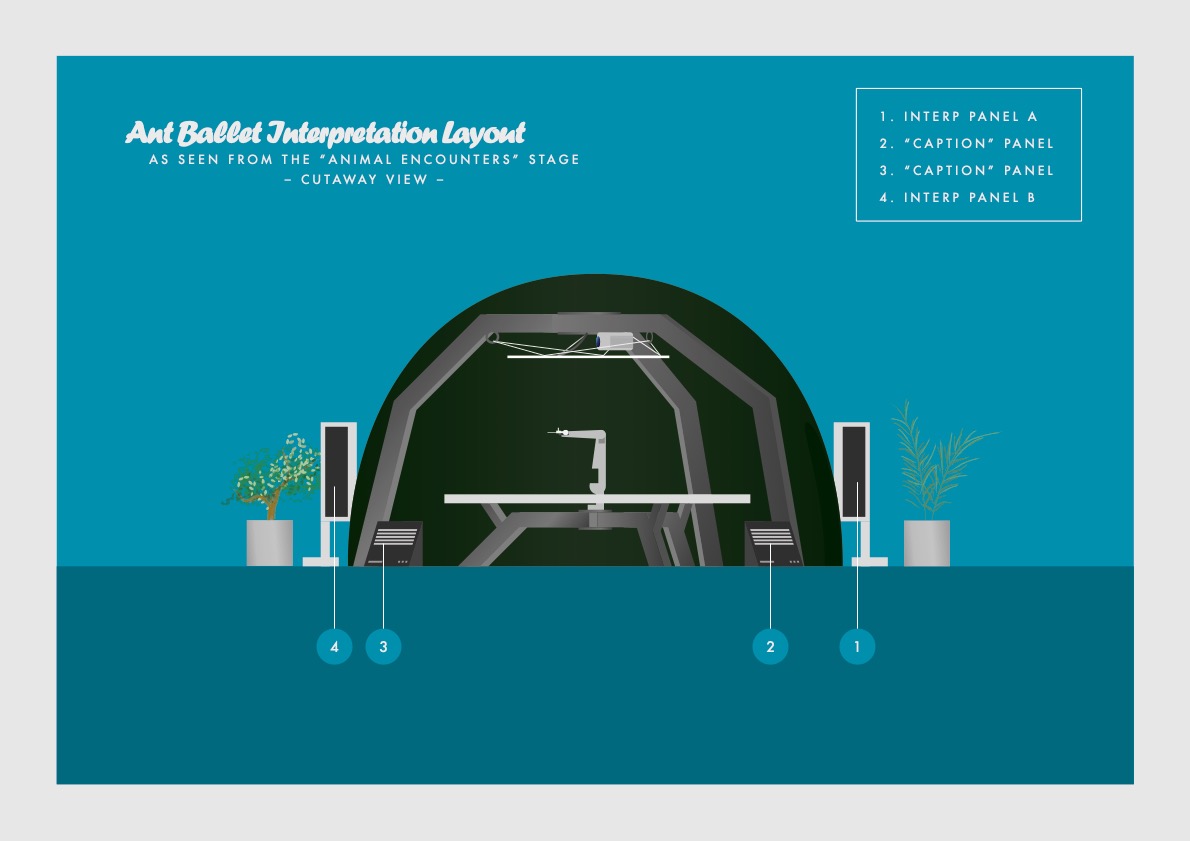

Ant Ballet culminated in a film and a series of objects, and was the first of my projects to place such an emphasis on narrative structure and performance.37 Once I had completed the experiment in Barcelona (where the necessary species of ant colony could be found), and used this to create a film, the project was exhibited at various places. The first exhibition outside of UCL, which took place after my MArch, was at the Zoological Society London (ZSL) London Zoo;38 here, lacking the ability to use real ants (for the same reasons that the experiment was completed in Barcelona – see the appendices), the installation consisted of a simulated version of ant movement, adapted from the ant simulation software I had already programmed as part of the experiment, projected onto a white table-top, with a robotic arm ‘spreading’ pheromones onto the table. The chassis of the original Ant Ballet machine was used, but with a newly-made table surface, light ring and robotic arm. Virtual ants would form trails, and the arm would ‘spread’ virtual disruptive pheromones (the effect of which could be seen in the projected image), and the ants would disperse, only to lay new pheromone trails over time. At the edge of London Zoo’s BUGS building, beside a bright floor-to-ceiling window, the installation was housed in a dark tent, lined with theatrical blackout fabric, with three viewing holes.39 The table, two metres in diameter, had approximately one metre of clearance to the side of the tent, and the audience had to get close to the viewing holes in order to see inside (Figure 1-7). The film was projected onto the side of the tent, whilst inside and around it, signs explained both the function of the machine, and scientific knowledge about ant behaviour. Part of the terms of an installation in the Zoo was that it had to be educational, and highlight the conservation work that ZSL’s scientists do; therefore the information was designed to be easily understood by a young audience, and was light and friendly in tone.

The presentation of the project in this manner had a problematic impact on its public reception as an artwork: whilst the work itself (as captured in film and later print) succeeded in embodying an absurd diagram, this specific manifestation of the project did not.40 The absurd nature of the project, its diagrammatic qualities, and its inherent humour, were all lost beneath the veneer of educational entertainment.41 The reason is simple: although the project was produced in collaboration with scientists, in this particular presentation, the artistic intention became subservient to the scientific aspect. This was exacerbated by the inability to include real ants, in a setting that was directly opposite a live leaf-cutter ant exhibit. Visitors had the expectation of seeing live animals, and therefore, rather than being viewed a diagrammatic work of art, my installation was an underwhelming addition to an engaging zoological experience. Within the artistic context, the scientific nature of this project (both in terms of its collaborative aspect – with a team of organic chemists at UCL – and with regards to its setting at ZSL) led to the framing of the project in terms of ‘sci-art’. However, this was not my original intention: my goal had been to produce an absurd machine, which involved scientific collaboration, rather than a scientific collaboration whereby the outcome happened to be absurd.

The problematic relationship between art and science in ‘interdisciplinary’ projects has been subject to scrutiny by authors Georgina Born and Andrew Barry in a number of reports.42 In Art-Science, Born and Barry define the ‘emergent field of art-science’ as ‘part of a heterogeneous space of overlapping interdisciplinary practices at the intersection of the arts, sciences and technologies.’43 The sci-art field has gained prominence in recent years with a number of bodies established to fund projects involving artist-scientist collaboration: the Wellcome Trust has been a major funding source for such projects since its ‘Sciart’ programme was founded in 1996; the Sciart Consortium was formed in 1999 (joining the Wellcome Trust with ‘Arts Council England, the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, the Scottish Arts Council and the British Council’); and in 2003 Arts Council England and the Arts and Humanities Research Council formed the Arts and Science Research Fellowship programme.44 These organisations implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) refer to a perceived chasm between the arts and the sciences as a rationale for their existence. This idea was identified and explicated in C.P. Snow’s famous Two Cultures lecture of 1959, which remains influential to this day.45 Snow argues:

There seems then to be no place where the cultures meet. I am not going to waste time saying that this is a pity. It is much worse than that. Soon I shall come to some practical consequences. But at the heart of thought and creation we are letting some of our best chances go by default. The clashing point of two subjects, two disciplines, two cultures—of two galaxies, so far as that goes— ought to produce creative chances. In the history of mental activity that has been where some of the break-throughs came. The chances are there now. But they are there, as it were, in a vacuum, because those in the two cultures can't talk to each other. It is bizarre how very little of twentieth-century science has been assimilated into twentieth-century art.46

While Snow’s thesis calls for a bridging of the disciplines in order to forge new forms of knowledge, the benefits he outlines are distinctly scientific or technical, as opposed to artistic. Snow was seeking technical solutions to large-scale problems of his day (population growth, the Cold War, income inequality) through merging of disciplines, yet in doing so, he insinuates that art only obtains validation in the broader societal realm when it brings functional knowledge to society. This observation about the perceived process of artistic legitimisation that is seen to underpin sci-art collaborations is a starting point for both Born and Barry in Art-science and Paul Glinkowski and Anne Bamford in their analysis of the Wellcome Trust’s Sciart programme.47 As Barry et al. explain, similar attitudes are expressed in contemporary sci-art funding:

One of the key justifications for funding art-science, particularly in the UK, has been the notion that the arts can provide a service to science, rendering it more popular or accessible to the lay public or publicising and enhancing the aesthetic aspects of scientific imagery.48

This is exemplified by the Wellcome Trust’s funding, which is ‘explicitly intended to bridge the two cultures by enlisting artists to foster the public’s relationship with science.’49 As Glinkowski and Bamford state:

Working alongside the arts had helped to make science more accessible to the public, and had thus improved scientific communication. It was suggested that artists had, in some cases, helped to improve a perceived ‘image problem’ ascribed to scientists and to the scientific profession. [...] Artists working on [^Wellcome Trust-funded] Sciart projects were felt to have acted as a proxy for the public, opening up scientific practices to a wider gaze. By bringing into the public domain new perspectives on the work that was being conducted in laboratories and other places of science, it was suggested that artists were, in effect, acting as the ‘public’s representative’. A significant aspect of the artists’ contribution to ‘public engagement with science’ was thus as independent scrutinisers – asking questions and provoking insights that might not otherwise be possible, either from the perspective of the general public or from within the scientific community itself.50

Acting in this manner, art becomes a mouth-piece of science; a method of communicating scientific knowledge over artistic expression. The Ant Ballet installation in London Zoo exemplified this relationship; the diagrammatic absurdity of the project was a secondary message to the valid scientific knowledge that could be imparted to the public. It was disappointing to see the original artistic intention of the work diluted to this extent. However, this experience proved to be incredibly valuable as it exposed the impact that framing can have on the perception of an artwork, and prompted me to re-establish and theorise the original intention behind the project.. Presenting this particular project as sci-art, in a venue associated more with education than artistic expression, created a frame within which a public will only focus on the science. Within this environment, artistic content merely becomes a series of aesthetic choices through which science is communicated.

However, the potential of science-art collaborations is not limited to this imbalanced relationship model. Born and Barry argue that there is potential for new modes of knowledge that do not subjugate one discipline below the other:

We propose that art-science should be understood as a multiplicity, and that part of its interest lies in not being reducible to the imperative to render scientific knowledge more accessible or accountable. Indeed art-science poses definitional and conceptual challenges since, while it exists as a practical, intentional category for artists and scientists, cultural institutions and funding bodies, it forms part of a larger, heterogeneous space of overlapping interdisciplinary practices at the intersection of the arts, sciences and technologies – including new media art and digital art, interactive art and bio-art [...] while these domains abut adjacent interdisciplinary scientific and technological fields from robotics, informatics, artificial and embodied intelligence to tissue engineering and systems biology. There is thus a great deal of activity but little codification; ‘art-science’ amounts to a pool of shifting practices and categories that are themselves relational and in formation.51

Fortunately, I was able to re-frame the project shortly after the London Zoo installation in a way that resisted the ‘codification’ Born and Barry highlight. In May 2012, I produced an installation for the FutureEverything festival in Manchester.52 I had first made contact with FutureEverything a few years previously, when a project I had worked on received a runner-up prize at their inaugural awards.53 The festival itself has a broad remit, and has grown from being an avant-garde music festival (entitled FutureSonic, established in 1996) to being at the forefront of critical questions in technology, staging an art exhibition and conference alongside a series of music and film events in and around Manchester.54 The festival featured artists working in disparate genres but united by their engagement with technology, attracting an audience consisting of the general public, as well as media and technology specialists (MediaCity, the main BBC studios in the North of England, and Granada Studios are both located nearby). Having realised the issues with the ‘framing’ of Ant Ballet as at the Zoo, I worked with FutureEverything’s curation team to ensure that the project itself would be presented with the emphasis on artistic intention.55 I made three new films and built a new, aesthetically simplified version of the machine.56

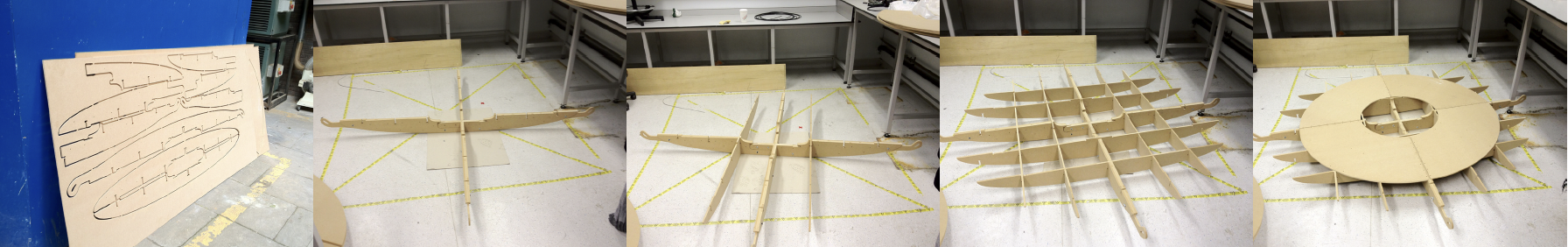

The exhibition took place on the top floor of the 1830 Warehouse, a Grade I-listed building within the Science Museum’s Museum of Science and Industry. The historic setting created several logistical challenges, as artists were prohibited from mounting works that could potentially damage or alter the building in the process of installation (such as screws). The space consisted of four large projected films along one wall, each approximately 2.5m wide, with a round machine, 2m in diameter, suspended approximately half a metre above the floor in the middle of the room. The machine was a specially-made maquette of the original Ant Ballet machine (as used in the original Barcelona experiment and at London Zoo), but aesthetically simplified so that it appeared to be merely a white floating surface, with a robotic arm which would only become visible when it was disrupting the virtual ant trails. The robotic arm itself was minimalist, consisting of black aluminium tubular rods, servos and bespoke 3D-printed nylon connectors. At the end of the arm, the pheromone-spreading actuator, instead of being a replica of the real pheromone spreaders, was a conductors’ rod. The simulation showed virtual ants, each a white pixel, moving on the surface of the machine and laying and optimising green trails. When the machine ‘activated’, a spotlight would illuminate the conductors’ wand, which would tap and distribute virtual pheromones. The ants’ behaviour could instantly be seen on the table: the well-formed trails would break apart, the pheromones would evaporate and disappear, and the ants would begin again. The conductors’ wand would operate once every few minutes – enough that the ants could effectively recuperate, and that a casual audience member would have enough time to observe both the formation of ‘natural’ trails and the disruption of the trails by the machine. The machine also dispensed with the Dr. Strangelove-inspired light-ring that was used in the original machine and its London Zoo counterpart, instead using the high-powered projector suspended above to illuminate the table surface, and the arm when the machine was activated.

Across the four screens, four films played on looped projections. Whilst each film was not playing, its screen would be illuminated in a pastel colour with a one-word title such as ‘Making’ or ‘Info’.57 The screens were inspired by interface monitors from Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey (in which the an entropic plotline and breakdown in communications emulate the absurdist overtones of Dr Strangelove) and featured similar graphics, animation, and sparse wording to those on the fictional space-ship controlled by the computer HAL (I had visited the Kubrick Archives to investigate how the original interfaces had been animated).58 Each film presented an aspect of the project: the first focused on control, and the emergent properties of pheromone trails as opposed to hierarchical control systems; the second presented infographics which explained the ant movements; the third focused on the making of the project; and the final film was documentation of the Barcelona experiment and the only video with sound. The intention behind this arrangement was to highlight the referential and diagrammatic nature of the installation. The Barcelona film referred back to the original experiment, but played its 90 second loop only once every three minutes; the three silent films, on the other hand, were made intentionally to explain and emphasise the machine in the centre of the room as a simulation of ant behaviour, rather than a mere copy of the initial scientific experiment. In other words, the installation emphasised the absurd idea underpinning the project, rather than the scientific specifics of the ant experiment: the machine was presented as a map to the territory of the real machine. Unlike in the ZSL exhibition, FutureEverything gave me the opportunity to highlight the absurdist and metaphorical aspects of the project by distancing the work from the live insects, and therefore repositioned the scientific aspect as a complimentary, rather than dominant, facet of the artistic practice.

I spent time in the opening week of the exhibition observing how the audience engaged with the machine and the films. The installation was the first ‘room’ in the gallery, and the layout drew people through the space. Most spent around 3-5 minutes watching films – some flitted between films and machine, whilst others worked their way through the films sequentially. The sparse timing of the pheromone-releasing machine created a spectacle every time it activated, and the machine itself was often a hub around which the audience gathered (even whilst watching the screens). There were numerous factors which made this installation a success in contrast to its earlier exhibition. The sheer amount of space, the ability to frame the messages the project conveyed, and effectively choreograph an audiences’ movement through the room through the interplay of films and machine, all played a role.

The project also garnered media attention. The day after the exhibition launched, I was interviewed by BBC News, as well as Brazilian and Iranian television networks, and national magazines, and the project was featured on numerous blogs worldwide.59 Whilst such media attention is not by any means an indicator of the quality of work, the role it plays in promotion of an artist cannot be underestimated. The spreading of Ant Ballet (and in particular the projects’ main video) via the internet led directly to later commissions, including the residency at the Palais de Tokyo which enabled other projects in this thesis (Scriptych, 86400, 24fps Psycho, Network / Intersect) to take place.

Before I began the PhD thesis, I had intended to continue working on the Ant Ballet project, refining the design, developing the technical and theoretical aspects in order to create multiple permutations and iterations of the machines, and create performances, installations and films of the same theme. During the initial months of my thesis research, I worked on a project with my collaborator Dr. Sumner in which I built technical equipment to test whether British garden ants (Lasius niger) are attracted to electricity, as has been anecdotally reported, which was then tested in a study at the Institute of Zoology by an undergraduate student. It was through careful analysis of my experiences in this project, as well as the failed and successful installations, which led me to realise my earlier arguments about the importance of the frame. I took the conscious decision to move away from the field of sci-art for the next few projects in order that I could focus on the creation of absurd diagrams.

Chapter Conclusion#

In this chapter, I have discussed the development of two projects, and the role that framing has on the perception of work. I have argued that in the case of Ant Ballet, the sci-art moniker (and its associated terms) was not useful in framing the project, leading to the creation of an unsuccessful installation at London Zoo. The specific relationship between science and art within Sci-art practice can, of course, exist in multiple permutations. As has been discussed, Born and Barry highlight three modes as being particularly prevalent.60 The first, refers to the appropriation of scientific knowledge to justify artistic production. Closely related to this is the second permutation, involving the production of artwork whereby the intention is to communicate pre-existing scientific knowledge: ‘Science is conceived as finished or complete, and as needing only to be communicated, understood or applied, while art provides the means through which the public is mobilized or stimulated on behalf of science.’61 This latter is an approach I strongly disagree with and have tried to avoid in my own work. Science is a continuum of knowledge, formed through consensus and continual posing of theories.62 As Kuhn has described it, normal science is a ‘puzzle-solving’ activity, one which establishes myriad smaller problems to be solved in order to get closer to proof of a larger theory.63 Scientific knowledge is not always agreed upon: ‘History suggests that the road to a firm research consensus is extraordinarily arduous.’64

The third mode of science-art partnership, which is strongly advocated by Born and Barry, denotes a mode of collaboration that instigates the generation of a new form of knowledge . They cite the work of Barbara Cassin and Hannah Arendt to claim that this mode of art-science practice could produce knowledge that is different from either discipline. Art-science, as they see it, is a public experiment, which they define using the Greek term epidexis: ‘the art of “showing” (deiknumi) “in front” (epi), in the presence of a public, to make a show.’65 They explain:

As a form of epideixis, public experiments do not so much present existing scientific knowledge to the public, as forge relations between new knowledge, things, locations and persons that did not exist before – in this way producing truth, public, and their relation at the same time.66

Whilst Ant Ballet, being created with an absurd diagram in mind, and acting through performance itself, may fit into this category of work, I believe it is actually closer to the work of Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove. The project is an artwork, displayed in a performative manner to the public, which uses scientific knowledge, experts, and methodologies to convey an absurd diagram to a public. First and foremost in the project lies the absurd intention; the fact that the project uses scientific methods, necessitating collaboration with scientists, should not change this. Far from weakening the project, or the nature of the collaboration itself, not defining the work as ‘sci-art’ enables the interested observer to find out more about the project if they desire (through publications such as New Scientist or Bio Art: Altered Realities),67 or engage with the work as it was intended.

This argument is exemplified in the Jorge Luis Borges short story On Exactitude in Science, in which an empire becomes so obsessed with cartography that it builds a 1:1 map of its territory; the map is useless, and ends up a tattered historical relic. Jorge Luis Borges, ‘On the Exactitude of Science’, in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin, 1998), 325.

-

Both of the main Ant Ballet installations that are discussed towards the end of this chapter (London Zoo and FutureEverything) were completed after I had graduated from the Bartlett, and FutureEverything in particular represented a significant extension to the pre-existing body of work which has not been presented for examination before. ↩

-

This does not mean that my practice rules out the idea of collaboration with scientists, or applying scientific principals or methodology to my work, but rather that the intention of work should not be made secondary to the communication of scientific knowledge. This is clarified in the section on Ant Ballet at London Zoo and FutureEverything exhibitions. ↩

-

G. Bateson, ‘A Theory of Play and Fantasy’, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 13. printing. (Ballantine, 1985), 177–93. The essay was originally delivered as a lecture in 1954. ↩

-

Note that Bateson’s conceptions of frame are similar to, but distinct from from Minksy’s ‘frames’ in Marvin Minsky, ‘A Framework for Representing Knowledge’, 1 June 1974, DSpace@MIT - Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL) - Artificial Intelligence Lab Publications - AI Memos (1959 - 2004), https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/6089. ↩

-

Bateson, ‘A Theory of Play and Fantasy’, 185. Note: Bateson’s italics. ↩

-

Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotlian Systems and General Semantics, Fifth edition, second printing (Brooklyn, N.Y., USA: International Non-Aristotelian Library, Institute of General Semantics, 2000), 58. ↩

-

Korzybski, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotlian Systems and General Semantics, 58. ↩

-

Bateson, ‘A Theory of Play and Fantasy’, 188. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 192. ↩

-

Ibid., 193. ↩

-

Ibid., 192. ↩

-

Ibid., 193. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 192–93. ↩

-

Schank and Abelson’s script theory in turn contains references to Marvin Minsky’s ‘frame theory’, which Minsky in turn notes is partly based on Schank and Abelson’s work. Minsky makes no note of Bateson, however. Minsky cites Schank and Abelson’s separate works in his 1974 paper A framework for representing knowledge. Minsky, ‘A Framework for Representing Knowledge’, 1. Schank and Abelson in turn cite Minsky’s paper in both their initial joint conference paper on scripts (1975), and the later book Scripts, plans, goals and understanding (1977). Roger C. Schank and Robert P. Abelson, ‘Scripts, Plans, and Knowledge’, in Proceedings of the 4th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence-Volume 1 (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., 1975), 151; Roger C. Schank and Robert P. Abelson, Scripts, Plans, Goals, and Understanding: An Inquiry into Human Knowledge Structures (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1977), 10. ↩

-

Bateson discusses both traditional Balinese painting and Van Gogh, though not explicitly in relation to its psychological framing, elsewhere in Steps to an Ecology of Mind. ↩

-

Vivian Mercer, ‘The Uneventful Event’, Irish Times, 18 February 1956; Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts, En Attendant Godot (London: Faber & Faber, 1956). ↩

-

Lucas would go on to produce successful franchises such as Star Wars and Indiana Jones. Note that in THX-1138, the character does eventually find others; the film may have been a little tedious otherwise. George Lucas, THX 1138, Crime, Drama, Sci-Fi, (1971). ↩

-

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (London: Penguin Books, 2008). For more dystopian sci-fi, see for example, Yevgeny Zamatin’s novel We (1921/4), Ayn Rand’s Anthem (1937), films such as Metropolis (1927), Logan’s Run (1976), Alphaville (1965). Yevgeny Zamyatin, We, trans. Bernard Guilbert Guerney (London: Cape, 1970); Ayn Rand, Anthem (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, ltd., 1969); Michael Anderson, Logan’s Run, Action, Sci-Fi, (1976). ↩

-

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, trans. Justin O’Brien, 12, from the 1955 translation ed. (London, England: Penguin, 1955). ↩

-

M. Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. A Sheridon (New York, NY, USA: Vintage Books, 1977), 200–228. ↩

-

Ibid., 200. ↩

-

Ibid., 204. ↩

-

Please note that much of the technical development work for the Godot Machine was completed during my Masters research. ↩

-

Ant Ballet had the working title of Physical Virus for several months. ↩

-

Examples include the residents of the town in Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, who one by one turn into rhinoceroses, against their will, and the two protagonists in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, who are continually waiting for a person they do not know for equally unclear reasons. Eugène Ionesco, Rhinoceros, trans. Martin Crimp (Faber & Faber, 2007); Beckett, Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts. ↩

-

Ant pheromones are used for conveying several types of information: sex, aggregation, dispersal, alarm, territory and surface pheromones all exist in various ant species. Sex pheromones bring ants together for the purpose of mating. (Brian D. Jackson and E. David Morgan, ‘Insect Chemical Communication: Pheromones and Exocrine Glands of Ants’, Chemoecology 4, no. 3 (1993): 126, doi:10.1007/BF01256548.) Aggregation pheromones simply ‘cause members of the same species to aggregate in a particular area [...] for mating or to a food source or a suitable habitat.’ (Ibid., 127.) Dispersal pheromones, also known as spacing pheromones, and used to regulate or prevent overcrowding of food sources, etc. (Ibid.) Surface pheromones, also known as cuticular hydrocarbons, these pheromones exist on ants’ body surfaces and allow them to identify which colony other ants belong to. This is particularly important for food exchange. (Ibid., 130.) ↩

-

One of the major authors on this subject is Marco Dorigo, who has published numerous papers detailing the systems that ants use and the computer models of these as applied to computer science challenges such as the travelling salesman problem. See for example: Marco Dorigo, V. Maniezzo, and A. Colorni, ‘The Ant System: An Autocatalytic Optimizing Process’ (Technical report, 1991); Marco Dorigo, Vittorio Maniezzo, and Alberto Colorni, ‘Positive Feedback as a Search Strategy’ (Milan: Politechnico di Milano, 1991); A. Colorni, M. Dorigo, and V. Maniezzo, ‘Distributed Optimization by Ant Colonies’, vol. 142 (Proceedings of the first European conference on artificial life, Paris, France, 1991), 134–42; Marco Dorigo, Gianni Di Caro, and Luca M Gambardella, ‘Ant Algorithms for Discrete Optimization’, Artificial Life 5, no. 2 (1999): 137–72; M. Dorigo and T. Stützle, Ant Colony Optimization, A Bradford Book (Cambridge, MA; London, UK: Bradford Book, MIT Press, 2004). ↩

-

William Myers, Bio Art: Altered Realities (Thames & Hudson, 2015), 192–94. ↩

-

Stanley Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove (Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb), 1964. ↩

-

Kubrick himself appears to have been aware of this similarity: after the film’s release, he sent a press clipping reviewing the film entitled The Movie of the Absurd to the head of Polaris Productions. Stanley Kubrick, ‘The Movie of the Absurd: Press Clipping Sent from Staley Kubrick to Nathan Weiss’, n.d., SK/11/9/50, The Kubrick Archive, London College of Communication. ↩

-

Fred Kaplan, ‘Truth Stranger Than “Strangelove”’, New York Times, 10 October 2004, Online edition, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/10/movies/truth-stranger-than-strangelove.html. Note that one exception is the War Room itself. ↩

-

Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill, The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick, Great Filmmakers (New York, NY: Facts on File, 2002), 88; Kaplan, ‘Truth Stranger Than “Strangelove”’. ↩

-

Myers, Bio Art, 192. ↩

-

The exhibition was in the BUGS building at ZSL London Zoo from November 2011 until May 2012, curated by the insect-arts organisation Pestival. ↩

-

This was a compromise instated due to the extreme natural light levels in the room, and their impact on the projections. ↩

-

Myers, Bio Art, 192–95. ↩

-

This form of educational entertainment is sometimes given the portmanteau ‘edutainment’. See, for example, Greg Beato, ‘Turning to Education for Fun’, The New York Times, 19 March 2015, Online edition, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/20/education/turning-to-education-for-fun.html. ↩

-

See Andrew Barry, Georgina Born, and Marilyn Strathern, ‘Interdisciplinarity and Society: A Critical Comparative Study: Full Research Report’ (Swindon: ESRC, 2007); Andrew Barry, Georgina Born, and Gisa Weszkalnys, ‘Logics of Interdisciplinarity’, Economy and Society 37, no. 1 (February 2008): 20–49, doi:10.1080/03085140701760841; Georgina Born and Andrew Barry, ‘Art-Science’, Journal of Cultural Economy 3, no. 1 (2010): 103–19, doi:10.1080/17530351003617610; Andrew Barry and Georgina Born, Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, Culture, Economy and the Social (Taylor & Francis, 2013). ↩

-

Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’, 103. Sci-art is known by numerous monikers: the Wellcome Trust variously use sciart and sci-art; Born and Barry use art-science; Weszkalnys uses science-art. The terms all have rough equivalence. For the sakes of clarity, I will use sci-art unless quoting from a source who uses a different term. ↩

-

Ibid., 108.; see also Paul Glinkowski and Anne Bamford, Insight and Exchange: An Evaluation of the Wellcome Trust’s Sciart Programme (Wellcome Trust London, 2009), http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/stellent/groups/corporatesite/@msh_grants/documents/web_document/wtx057228.pdf. ↩

-

C. P. Snow, ‘The Rede Lecture, 1959’, The Two Cultures: And a Second Look (London: Cambridge University Press, 1964), 1964. For The Two Cultures in popular culture, see for example, BBC Radio 4’s coverage of Snow. Melvyn Bragg, ‘The Value of Culture: Two Cultures’, BBC (London, England: BBC Radio 4, 2 January 2013), http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01phhy5. ↩

-

Snow, ‘The Rede Lecture, 1959’. ↩

-

Glinkowski and Bamford, Insight and Exchange; Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’. ↩

-

Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys, ‘Logics of Interdisciplinarity’, 29. ↩

-

Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’, 108. ↩

-

Glinkowski and Bamford, Insight and Exchange, 9. ↩

-

Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’, 104. ↩

-

I must again thank Heechan Park for the help in constructing the exhibition. ↩

-

The project was called Open_Sailing (now Open_H20 and Protei), initiated by Cesar Harada. ↩

-

In 2012 FutureEverything’s festival included: a performance of Matthew Herbert’s One Pig, a musical show documenting the soundtrack of a pig’s entire life; sound installations by Daniel Jones and Matthew Bulley; interactive video work by Kasia Molga and Brendan Walker; thousands of small clay figurines being distributed across Manchester by artist Laurence Epps; conference presentations from Icelandic MP and WikiLeaks collaborator Brigitta Jonsdottir, and then-MP of Art and Culture Ed Vaisey. ↩

-

The key curator in the exhibition was Deborah Kell. ↩

-

I wish to thank Heechan Park again for his help in the construction of this machine. ↩

-

The first and third screens used a pastel pink background, whilst the second and fourth used a pastel turquoise. ↩

-

Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Film (Metro Goldwyn-Meyer, 1968). ↩

-

The exhibition also featured on the influential art blog We Make Money Not Art, and was subsequently featured in Wired Magazine, as well as others. Regine Debatty, ‘An Ant Ballet at FutureEverything’, We Make Money Not Art, 17 May 2012, http://we-make-money-not-art.com/futureeverything/; Jeremy Kingsley, ‘Colony Choreography: Making Ants Dance with Synthesised Pheromones’, Wired UK, 17 October 2012, http://www.wired.co.uk/article/colony-choreography. ↩

-

Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’. ↩

-

Ibid., 105. ↩

-

Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Fourth (University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩

-

Ibid., 42. ↩

-

Ibid., 15. ↩

-

Born and Barry, ‘Art-Science’, 116. The term epidexis was defined in the manner Born and Barry describe by Cassin, and discussed by Arendt. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Sandrine Ceurstemont, ‘Artificial Pheromone Controls Invasive Ant Dance’, New Scientist TV, 17 March 2012, https://www.newscientist.com/blogs/nstv/2012/03/artificial-pheromone-controls-invasive-ant-dance.html; Graham Lawton, ‘Fleadom or Death: Reviving the Art of the Flea Circus’, New Scientist 216, no. 2896–2897 (2012): 53–55, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(12)63266-7; Myers, Bio Art. ↩